Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore Story

On the north bank of the Singapore River is an eight-foot-tall statue of a man striking a stately pose, arms folded, gazing into the horizon. Stamford Raffles stands – according to the plaque attached to the plinth – on the ‘historic site’ where he first landed as an agent of the British East India Company on 28 January 1819 and, thereafter, ‘with genius and perception changed the destiny of Singapore from an obscure fishing village to a great seaport and modern metropolis’. Raffles – who is officially recognised as the ‘founder’ of modern Singapore – had a strong conviction that the tiny trading outpost he founded at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula would fulfil a destiny larger than its physical size. He was right. But he was not a nation-builder. He visited Singapore just three times, spending slightly more than nine months on the island across a period of three years. After founding the outpost, he spent most of his time elsewhere, in neighbouring Indonesia (then the Dutch East Indies). If Raffles boasted of Singapore as his ‘child’, it is fair to say he was an absent father.

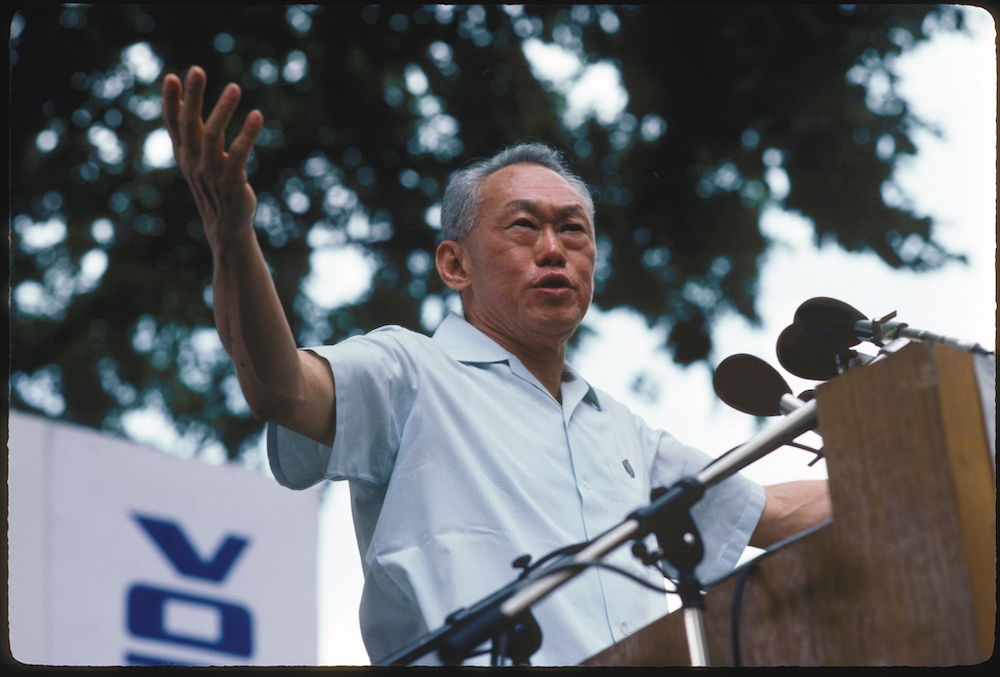

The story of Singapore’s ascent from ‘Third World’ to ‘First’, following its forced separation from Malaysia in August 1965, happened under the watch of another visionary, Lee Kuan Yew. In September 2023, Singapore celebrates the centenary of his birth. Reflecting on his life and achievements a few years before his death in 2015, Lee told a group of assembled journalists: ‘I have spent my life, so much of it, building up this country. There’s nothing more that I need to do. At the end of the day, what have I got? A successful Singapore. What have I given up? My life.’ Lee believed this: his 1998 autobiography was titled, simply, The Singapore Story. Since his passing, Lee has been honoured as the nation’s ‘founding father’.

Rise during fall

Lee grew up in a comfortable, but not rich, English-speaking Chinese family. His parents, brought together in an arranged marriage, belonged to the colony’s majority Chinese community. Like any Singaporean child, Lee mingled with children of other ethnicities and played with Malay friends. The eldest of four children, the young Harry Lee – his anglicised first name was added by his grandfather who admired the British, but later dropped by Lee – was a gifted student. Coming first at the Senior Cambridge examinations in Singapore and Malaya in 1940, Lee decided to study law in London. The Second World War precluded this and, with Britain at war, Lee accepted a scholarship to study at Raffles College, the colony’s leading tertiary institution in the arts and sciences. There, he became the college’s best student in mathematics, but not in English or economics, which were topped by another student, Kwa Geok Choo, Lee’s future wife.

War had torn Europe apart and was creeping towards Singapore. On 8 December 1941, the sleepy city was awakened before dawn by the blare of air-raid sirens to the stark realisation that Britain was now at war with Japan. With classes cancelled, Lee volunteered as a medical auxiliary. Less than three months later, he watched with bewilderment the rapid collapse of British Malaya, as demoralised British and Commonwealth troops beat a desperate retreat to their island citadel of Singapore, only to see their much vaunted ‘impregnable fortress’ fall on 15 February 1942.

The brutal Japanese occupation lasted for three-and-a-half years and profoundly affected the trajectory of Lee’s life, and that of the city. The occupation was very hard on the city’s inhabitants, especially its Chinese population which was suspected of being anti-Japanese. Before the invasion, many overseas Chinese had openly supported China in its prolonged war with Japan. The victorious Japanese army, which had fought in China, now sought revenge. Like many other Chinese men, Lee was ordered to report to a ‘screening centre’. Many of those who complied were loaded onto lorries and executed. Lee asked to leave the line in order to return to a friend’s dormitory to collect his belongings. He hid there and never returned. Had the Japanese guard refused his request, Lee could have been among the estimated 5,000 to 50,000 Chinese men who were unfavourably ‘screened’ by the Japanese and who perished in the Sook Ching (‘purge through cleansing’) massacre. ‘I will never understand how decisions affecting life and death could be taken so capriciously and casually’, he later reflected.

Before the war, Lee had considered himself apolitical. But the war – and the Japanese occupation – destroyed the myth that the British were a superior and invincible people with an inherent right to rule Asians: ‘In 70 days of surprises, upsets and stupidities, British colonial society was shattered, and with it all the assumptions of the Englishman’s superiority.’ In his memoirs, Lee described being slapped and forced to kneel for failing to bow to a Japanese soldier. Lee’s experience of British failures destroyed his reverence for them; his experience of Japanese brutality led him to abhor them. As he later wrote, he emerged from the war ‘determined that no one – neither the Japanese nor the British – had the right to push and kick us around’.

After the war, Lee left Singapore for England to read law at the London School of Economics. Disliking London, he moved to Cambridge University. By the time he graduated in 1949 with a double first with starred distinction, he was a changed man. While his stellar achievements at Cambridge gave him confidence in subsequent dealings with British officials, his experiences in England also forged a deeply anti-colonial sentiment. He never forgot Britain’s blunders during Singapore’s fall, nor the class and colour prejudices he encountered in Britain. Inspired by socialist ideals, he befriended political leaders in the British Labour Party and even campaigned on behalf of one of his Cambridge friends, David Widdicombe, a Labour candidate. His growing political involvement in England caught the eye of Singapore’s Special Branch, which added Lee to its watch list.

In 1950, Lee delivered a parting speech to the Malayan Forum, a London-based discussion club founded to deliberate the future of Malaya. Lee spoke of how returning Malayan students, schooled in British institutions, could lead the fight for independence and oversee a smooth transfer of power. Upon returning home to begin his legal practice, the 27-year-old law graduate found a city still reeling from the aftermath of war, battling a rising communist insurgency, and shuffling uneasily toward an uncertain post-colonial future.

Party time

Since 1948, a mainly Chinese-led communist insurgency, cloaked as an anti-imperialist revolt, had established itself across Malaya and Singapore. In Malaya, British troops battled communists in a jungle war that would last another 12 years. In Singapore, the city’s mostly Chinese population made it a major target for communist subversion.

Lee considered joining a political party but none suited his left-wing, anti-colonial convictions. Because of the communist insurgency, only pro-British, right-wing parties such as the Progressive Party had survived. In response, Lee assembled a group of like-minded English-educated activists who met in the basement dining room of his bungalow at 38 Oxley Road to ponder the merits of forming a party. Lee’s roles as barrister and would-be politician soon became inseparable as he took on cases, often pro bono, of unionists, civil servants and student groups who had got into legal skirmishes with the colonial government. High-profile cases brought him public attention and he became a sought-after legal adviser. Contact with the leftist Chinese students he represented opened his eyes to the dynamism and anti-colonial potential among Singapore’s Chinese-educated population, which the communists had been working on for decades. Ever pragmatic, Lee formed an alliance of necessity with the communists to gain access to their mass base.

On 21 November 1954, ahead of a legislative assembly election the following year, Lee and his group launched the People’s Action Party (PAP), committed to using ‘every constitutional means’ to hasten the end of colonial rule in Malaya. Lee’s ‘men-in-white’ – identified by their all-white party uniform to symbolise incorruptibility – duly elected him as their Secretary General. At the PAP’s first election in 1955, Lee’s token team did well, winning three of the four seats it contested, and Lee became de facto opposition leader in a shaky coalition government helmed by the Labour Front. In the legislative assembly, Lee attacked colonialism and called for its swift demise.

But the PAP was not united. Split within, a pro-communist faction, sceptical of the effectiveness of constitutional methods, advocated the use of united front tactics, and even violence, in toppling the colonial government. The internal power struggle ended after Lee expelled the pro-communists in 1961. The splintered group formed the Barisan Sosialis (Socialist Front) and remained a troublesome thorn in the PAP’s side into the late 1960s.

In 1959, the PAP, campaigning on a pro-independence agenda and a detailed plan to solve bread-and-butter issues, won a spectacular landslide victory to form the government of self-governing (but not yet independent) Singapore. Lee became its founding prime minister, an office he retained until 1990. Since 1959, the PAP has won every general election on the island.

Malay or Malaysian

Under Lee, Singapore became independent twice, once by choice, once not. Lee’s goal had never been an independent Singapore; he wanted a free Malaya that included Singapore, which had been constitutionally detached from the peninsula as part of controversial British postwar plans to reconstitute its Malayan dependency. Britain feared that Singapore’s inclusion would unbalance Malaya’s population in favour of the Chinese. The island’s separation was to have serious repercussions for its future. Lee did not believe that tiny Singapore could survive on its own, or that the British would grant the colony freedom when communists were waiting to take power. After Malaya achieved independence ahead of Singapore in 1957, Lee championed ‘independence through merger’ with Malaya as the only realistic strategy for Singapore’s future. He convinced the Malayan premier, Tunku Abdul Rahman, of the security and political merits of including Singapore in a wider federation under Malayan leadership that also comprised the British Borneo territories. Lee defended this merger abroad and at home against a ferocious campaign by the Barisan Sosialis, and conducted a keenly fought, if controversial, referendum, which he won decisively, on merger terms agreed between the two leaders. Incorporating Singapore, the new state of Malaysia came into being on 16 September 1963, Lee’s 40th birthday.

But hopes of Singapore playing a role in the new Malaysian nation were dashed almost as soon as they had begun. No Singaporean minister was invited to join the right-wing Malaysian cabinet. Tunku Abdul Rahman did not want another prime minister in his cabinet. Heightened political competition and tensions flared up over competing visions of what Malaysia represented – whether it was to be a Malay Malaysia, where political power was jealously vested in a Malay-led and privileged central government; or a Malaysian Malaysia, where multiracial ideals were upheld.

In 1964, deadly Sino-Malay race riots broke out in Singapore. Lee blamed the riots on incitement by radical Malay activists hoping to undercut the appeal of the PAP’s socialist agenda to young Malays within Singapore and Malaya. ‘They wanted us to confine ourselves to Chinese voters and stop appealing to the Malays’, he later said: ‘The Malay electorate was out of bounds to non-Malay parties like the PAP.’ As relations slumped and a war of words became more and more heated, Tunku Abdul Rahman decided that removing Singapore from Malaysia was the only way to contain a potentially explosive situation. For their part, PAP leaders appeared set on leading a newly formed Malaysia-wide multiracial coalition to challenge Tunku’s government and its weaponising of race. Amid calls for his arrest to nip the PAP’s ‘Malaysian Malaysia’ movement in the bud, Lee secretly set his finance minister, Goh Keng Swee, to work on a deal with his Malayan counterparts for Singapore’s disengagement from federal affairs. But Goh exceeded his brief. He pressed instead for separation, convinced that the political cost of merger was dreadful and the economic benefits non-existent. Lee supported the move, which Tunku backed. With no better offer on the table, the Singapore premier, with great difficulty, persuaded his senior Malaya-born PAP ministers to accept separation and avert a bloody headlong collision. On 9 August 1965, Lee delivered a press conference announcing the separation, weeping at the shattering of his Malaysian dream. After less than two years, Singapore was out of Malaysia and independent for a second time.

‘First World oasis’

Independence was as sobering as it was cathartic. In Singapore’s Chinatown, relief at the end of the altercation was celebrated with firecrackers. But this light-hearted response belied the grave situation Singapore faced. ‘I have a responsibility for the survival of the two million people in Singapore’, Lee told foreign correspondents five days after separation. Lee was faced with the task of building a nation that would prove his earlier thesis wrong: that a small, vulnerable, independent Singapore, bereft of its Malayan hinterland, could survive. ‘Ten years from now’, he declared weeks later, ‘this will be a metropolis. Never fear!’

Within ten years it was. The PAP government, led by Lee, embarked on a novel strategy, using multinational corporations as agents of economic development at a time when many developing postcolonial nations shunned them for being exploitative. Interventionist and pro-business policies transformed the city-state into a leading financial, aviation and shipping hub, a ‘global city’ with the world as its hinterland. No effort was spared to promote Singapore overseas as an efficient and hassle-free investment destination, offering favourable industrial infrastructure and generous tax breaks and subsidies. Additionally, Lee galvanised domestic support for his social programmes, underpinned by the values of multiracialism, meritocracy, equality and rule of law. Over the following decades, Lee built a strong government that was backed by a competent and virtually corruption-free civil service, provided affordable world-class public housing making Singaporeans a nation of homeowners and created a well-equipped, modern defence force from scratch (with Israeli help) based on mandatory conscription for men. Drawing on his wide network of friends and world leaders, who valued his astute assessments of Asia and the world, Lee enlarged the nation’s strategic space to give big powers a stake in its continued survival and security. He fussed over every detail and imperfection, however minor, and imbued Singapore with his personal attributes: an openness to ideas and an emphasis on discipline, order and cleanliness. Singapore was to be his lush ‘garden city’, a First World ‘oasis’ in a Third World region.

Lee succeeded because he was backed by an exceptionally able team of ‘lieutenants’, but also because he built a deep reservoir of trust with Singaporeans over his long tenure. A charismatic speaker in English, Mandarin and Malay, Lee persuaded and cajoled Singaporeans to work with him on his national project. He lived frugally – his home was spartan, his office unadorned. Singapore survived its early years and became one of the most stable, safe, cosmopolitan and wealthy countries in Asia, enjoying a role and influence well out of proportion to its size. By the time Lee stepped aside as prime minister in 1990, Singapore’s GDP per capita had risen to around US$13,000, up from US$500 in 1965, surpassing South Korea, Israel and Portugal. Lee continued as senior minister and then minister mentor, before resigning from the cabinet in 2011. His death in March 2015, aged 91, was met with a nationwide outpouring of grief and gratitude. An estimated 1.5 million Singaporeans attended his lying in state to bid farewell to the nation’s strict father who once said he would rather be feared than loved.

Benign dictator?

Lee’s legacy, however, is not without its critics. Among the charges are that the PAP’s record of undefeated electoral successes since 1959 has turned Singapore into a one-party dominant state – perhaps even a dictatorship – with no tolerance for political dissent or parliamentary opposition. The heavy hand used against challenges to Lee’s authority and his conception of social order – curbing free speech and assembly, muzzling a free press, bankrupting opposition politicians by lawsuits (often for libel, which Lee won) and sanctioning detention without trial – is evidence of the dark side of Lee’s legacy.

For Lee, such ideological subtleties did not matter. ‘Do I need to be a dictator when I can win, hands down?’ he asked one American interviewer. Lee sensed a more sinister reason for the criticisms he faced, especially those from the West: an unspoken fear that Singapore’s success was proof of what enlightened authoritarianism can achieve where liberal democracy cannot. Does Singapore’s success justify the darker parts of Lee’s record in the ‘trade-off’ between prosperity and freedom? Lee never believed Western liberal democracy to be a universal good; its only virtue, he argued, was to change governments without violence. The essence of politics to him was not elections, but good governance and ensuring Singapore’s survival. ‘What political party helps an opposition to come into power?’ he probed. ‘Why should we not demolish them before they get started?’ Lee could be notoriously Machiavellian.

Monumental

As Singapore commemorates the 100th anniversary of Lee’s birth on 16 September 2023, no full-sized statue has been built to honour him (busts, however, are a different story; two have been publicly displayed with his permission). This is in accordance with his wishes. Lee was adamant that his Oxley Road home – the birthplace of the PAP – be demolished after his death to prevent it from becoming a museum. He worried that a personality cult around him would be detrimental to Singapore’s future. He may – or may not – have his wish. Since his death, Oxley Road has been the focus of an ongoing family feud involving Lee Hsien Loong, Lee’s eldest son and Singapore’s current prime minister, and his two younger siblings over the demolition of the house. The younger Lees accuse their brother (who has recused himself from cabinet deliberations on the property) of wanting to benefit politically by avoiding the demolition of their family home.

Lee did not believe the PAP would rule forever, even if he was scrupulous in bringing in new blood to perpetuate its political longevity. But the PAP and independence are not his only legacies. In his eulogy to his father, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong referenced the Latin epitaph on the grave of Sir Christopher Wren in St Paul’s Cathedral: ‘si monumentum requiris, circumspice’ (‘if you seek his monument, look around you’). ‘To those who seek Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s monument’, he added, ‘Singaporeans can reply proudly: “Look around you.”’

No comments: