France in Rhodesia: A Secret History of African Decolonisation

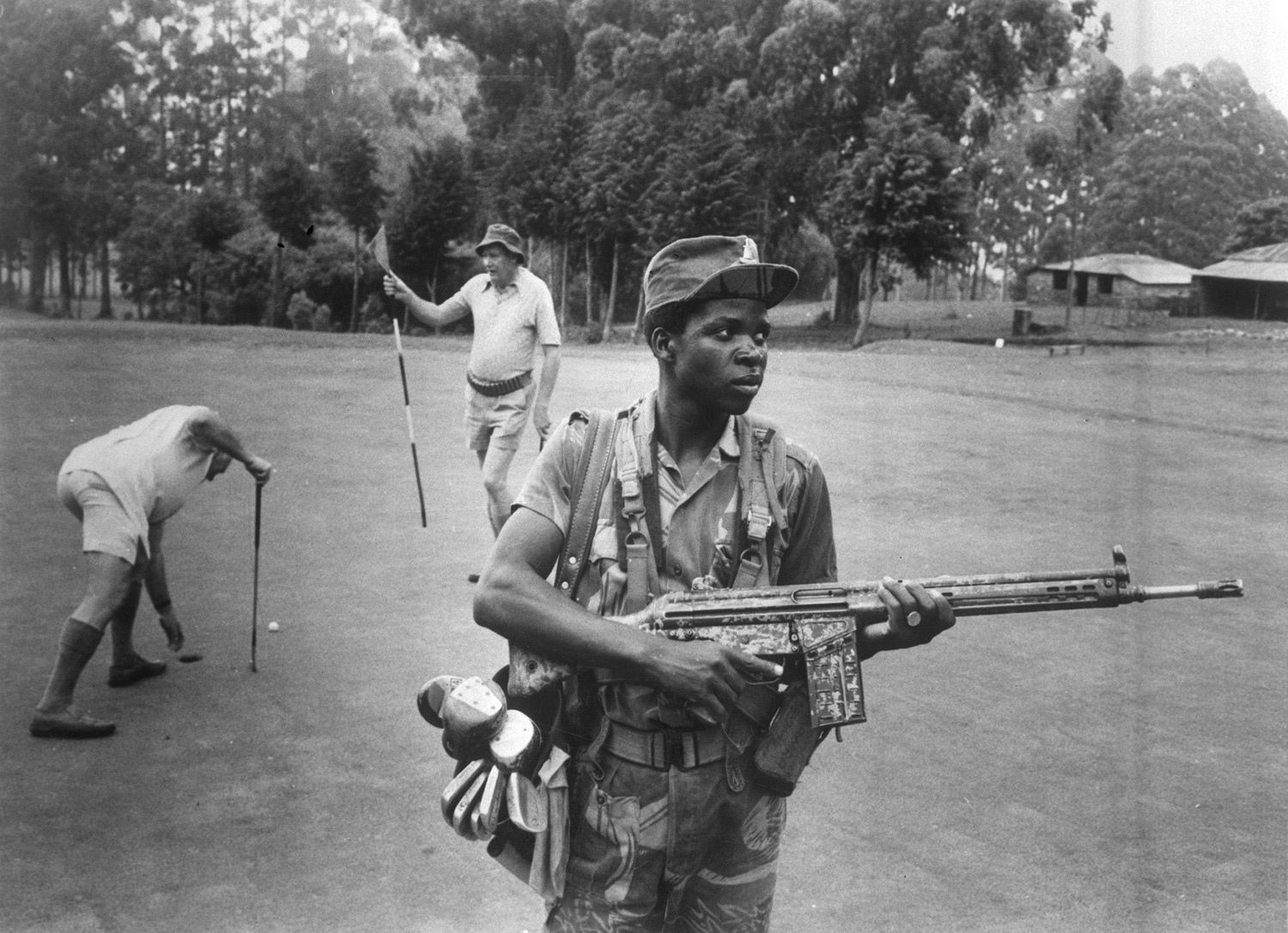

An armed guard provides security for white Rhodesian golfers at the Leopard Rock Hotel, Manicaland, 1978. Eddie Adams / Press Association ImagesIf recent revelations surrounding the 'secret archive' of Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) documents have done anything, it is to underline how much is still unknown about the history of the British Empire. With over a million documents alleged to be hidden from the public and historians alike by the British government, it is apparent that the history of Britain's colonial exploits may require substantial revision.

An armed guard provides security for white Rhodesian golfers at the Leopard Rock Hotel, Manicaland, 1978. Eddie Adams / Press Association ImagesIf recent revelations surrounding the 'secret archive' of Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) documents have done anything, it is to underline how much is still unknown about the history of the British Empire. With over a million documents alleged to be hidden from the public and historians alike by the British government, it is apparent that the history of Britain's colonial exploits may require substantial revision.

When one moves beyond a UK-centred approach to examine connections between colonial empires, the number of gaps in the existing picture of Britain's imperial past increases still further. Little is known, for example, about the part played by France in the decolonisation of Anglophone Africa and its aftermath. Yet, as a re-examination of the history of Southern Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) reveals, France played a significant – and frequently overlooked – role in the end of British rule on the African continent.

At 11 am GMT on November 11th, 1965 Ian Smith, prime minister of Rhodesia and leader of its white minority government, announced the colony's UDI from Britain. This move, deliberately timed to coincide with the precise moment that Armistice Day was commemorated in the UK, was conceived by Rhodesian-born Smith and his supporters as a way of preserving Christian 'civilisation' in Africa in the face of a perceived moral decline of the West, the encroachment of communism and the spread of corruption across the continent. The desire to maintain the privileged 'Rhodesian way of life' also underpinned this act of rebellion by a small, but influential, settler minority, many of whom had only migrated to southern Africa in the 20 years following the Second World War and maintained close ties with family and friends in the UK.

Ian Smith, prime minister of Rhodesia, signs his country's Unilateral Declaration of Independence, November 11th, 1965. Alamy

Ian Smith, prime minister of Rhodesia, signs his country's Unilateral Declaration of Independence, November 11th, 1965. Alamy

UDI set Rhodesia on a collision course, not only with its colonial rulers, but also with an international community increasingly committed to the eradication of colonial rule across the globe. It also significantly delayed the introduction of majority rule to this landlocked territory, with Zimbabwe not gaining official independence from Britain until April 18th, 1980, more than 23 years after Britain formally began decolonising its African empire by granting independence to the Gold Coast (Ghana) in 1957.

On the surface, the official French response to UDI appears far from extraordinary. The French government immediately condemned the actions of Smith and his supporters and refused to acknowledge the validity of a white-ruled Rhodesia, independent from Britain. The French consul and commercial attaché stationed in the Rhodesian capital, Salisbury (now Harare), were promptly recalled and the French ministry of foreign affairs openly affirmed its support for the programme of economic sanctions introduced by the UK government in an attempt to bring the rebellious Rhodesians to heel.

Yet behind this public position of opposition to UDI and the statements of cooperation with the UK authorities, there is a more complex picture of French reaction to this monumental crisis as Britain attempted to draw a line under its colonial ventures on the African continent. In contrast to Britain's difficulties in Rhodesia, France had, by 1965, decolonised all of its sub-Saharan colonies with the exception of Djibouti. Moreover, in spite of the violence that had characterised France's eight-year long, ultimately unsuccessful struggle to retain hold of the North African territory of Algeria, France fostered a much better reputation in Africa than Britain, frequently presenting itself as the 'champion' of black Africans and the Third World more widely. The divergence of Britain and France's African fates only grew as the UK government came increasingly under fire, at home and on the world stage, for its failure to introduce majority rule to Rhodesia, as well as its perceived intransigence over the persistence of apartheid in another of its former colonies, South Africa.

A supporter of the Smith government delivers election campaign posters, 1964. Express / Getty Images

A supporter of the Smith government delivers election campaign posters, 1964. Express / Getty Images

These contrasting experiences, combined with the long-standing Anglo-French rivalry in Africa, which can be traced back to the French humiliation at the hands of the British at Fashoda in 1898, mean that it is unsurprising that, behind official indignation at UDI, a hint of glee characterised the French response to Britain's troubles in southern Africa. Reports housed in the archives of Jacques Foccart, the chief adviser to French governments on African policy after 1960, described the UK government's policy in Rhodesia as 'incoherent' and characterised by 'multiple errors'. Furthermore, from a French perspective, Britain's mistakes in Rhodesia were not an isolated malfunction in the British decolonisation process, but part of an ever-lengthening list of British failures on the African continent, which also included South Africa, Tanzania, Nigeria and Ghana.

Even more satisfying for the French was the way in which the 'cruel failings' of Britain's decolonisation created new opportunities for France in regions of the African continent formerly dominated by the British. This included South Africa, where disagreements between London and Pretoria over apartheid, epitomised by South Africa's departure from the Commonwealth in 1961, created new openings for France, particularly in the economic sphere. French smugness about this shift in their favour is apparent in one French source that describes British 'worry' and 'bitterness' about its declining stature in South Africa, in contrast to France's growing position of strength.

The decline of British fortunes in southern Africa and the parallel rise for France was equally apparent in the Rhodesian setting. Even before UDI was declared, Rhodesians identified France as an important partner in their efforts to break free of British dominance, particularly as it offered potential new markets for their exports and alternative sources of investment. After 1965 many white Rhodesians continued to view France as an important ally in their struggle to 'go it alone'. Ian Smith wrote to French presidents Charles de Gaulle (1958-1969) and Georges Pompidou (1969-1974) on at least six occasions after UDI, openly expressing white Rhodesia's fraternal feelings towards France, as well as its hopes for further French support. Moreover, in a letter to de Gaulle from July 1968, Smith explicitly stated his belief that France was poised to fill the vacuum left by Britain in Rhodesia.

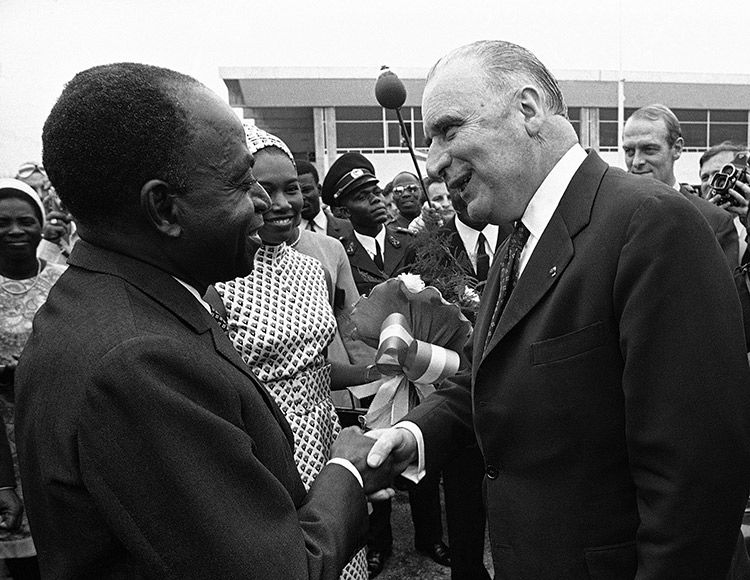

French President Georges Pompidou meets Felix Houphouet-Boigny, president of Ivory Coast, Abidjan, 1971. Press Association Images

French President Georges Pompidou meets Felix Houphouet-Boigny, president of Ivory Coast, Abidjan, 1971. Press Association Images

Across Rhodesian settler society there was a perception that France was sympathetic to their plight and might, in the future, offer more formal support. P.K. van der Byl, the South African-born politician and one of Ian Smith's closest supporters, believed that France would 'be prepared to do whatever she can to further trade and harmonious relations' and sustained hopes throughout the UDI period that France might accord Rhodesia formal diplomatic recognition. The Rhodesian press contained optimistic accounts of France's position towards UDI, such as reports alleging French opposition to the UK government's foreign policy and equating this opposition with sympathy for the white cause. Rhodesian confidence was also recorded in British newspapers: a feature on 'Rhodesia at war', published in the Guardian in 1966, included a discussion of how many white Rhodesians believed France would offer support to Smith's regime.

It is tempting to dismiss the Rhodesian representation of France as an ally as the delusions of an isolated and inward-looking population, influenced by a highly censored press. Certainly the UK government did not take these reports particularly seriously, with Downing Street dismissing them as 'Rhodesians whistling to keep their spirits up' and Whitehall claiming that the idea that France might offer diplomatic support to Rhodesia was 'wishful thinking on the part of the Rhodesians'. Yet French backing of Rhodesia was not entirely imagined, with both individuals and groups, some of whom had ties to the French state, providing Rhodesia with real assistance.

The principal means by which the UK government sought to bring the Rhodesian rebels to heel was through economic sanctions. However, the trade embargo largely failed to achieve its objective due to the numerous external actors who were willing to defy legislation by continuing to trade with Rhodesia. Apartheid South Africa and, until its independence from Portugal in 1975, Mozambique, were at the forefront of this illegal trade. Yet, businesses based in other western countries, including the UK, the US, Japan, West Germany and France, also breached the international trade embargo.

After UDI, French businessmen remained a common sight in Salisbury and French companies continued to buy Rhodesian goods, including tobacco, sugar and metals. French purchases from Rhodesia actually increased in the years immediately following UDI, with France importing 200 per cent more Rhodesian merchandise in the first three months of 1967 than it had done in the same period in 1966, including a 106 per cent rise in purchases of unembargoed commodities such as diamonds and precious stones.

French companies also remained important suppliers of goods to Smith's illegal regime. A visible French presence in Rhodesia after 1965 was to be found on the roads, with French estimates suggesting that 50 per cent of all cars driven in Rhodesia during the UDI period were made by one of two French manufacturers: Renault and Peugeot. Moreover, at least some of the petrol needed to fuel these automobiles came from French suppliers, with the Compagnie Française de Petrole (CFP) and its subsidiary, Total, providing oil that was transported overland to Rhodesia from Mozambique and South Africa.

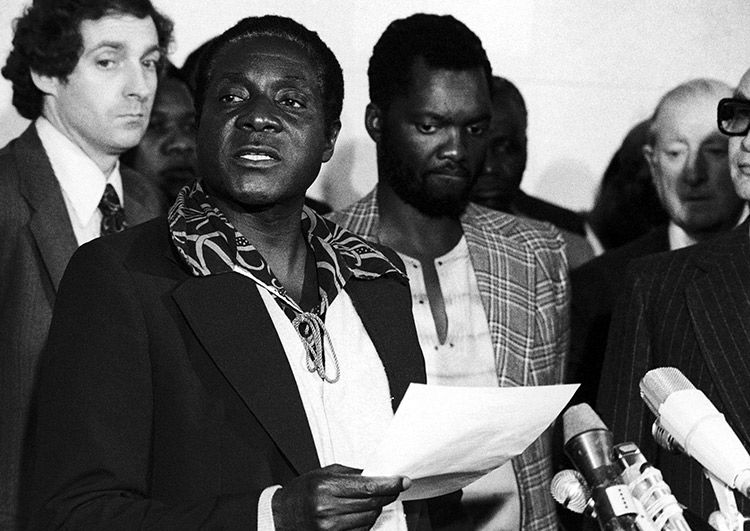

Robert Mugabe, future president of Zimbabwe, pushes his claim for the leadership of ZANU in October 1976. Horst Faas / Press Association Images

Robert Mugabe, future president of Zimbabwe, pushes his claim for the leadership of ZANU in October 1976. Horst Faas / Press Association Images

As well as helping to maintain the high standard of living for ordinary white Rhodesians, French companies also aided the physical defence of white rule. A guerrilla insurgency was launched in 1972 by the military wings of the two competing factions of the Zimbabwean nationalist movement: the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), led by Ndabaningi Sithole and Robert Mugabe; and the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), led by Joshua Nkomo. From the outset, French arms were vital to counterinsurgency efforts led by the Rhodesian Security Forces, with at least 50 French-manufactured Alouettes in the service of the Rhodesian Air Force (RhAF) between 1965 and 1980. The Rhodesians also had access to Mirage FI planes and Maxtra rocket launchers, leading one Zambian press report from 1977 to conclude that 22 per cent of all military material used by the RhAF was of French origin. Numerous French companies evaded the international trade embargo, therefore and, in doing so, contributed directly to efforts to maintain white rule in Rhodesia.

***

What is distinctive about French sanctions busting in Rhodesia is not its extent – British and US companies were probably more prolific – but the degree and nature of French government involvement. Although powerful business lobbies did influence the UK and US governments to turn a blind eye to illegal Rhodesian commerce carried out by British and American companies, French state complicity went deeper than this, to the heart of French involvement in Africa in the post-independence era.

After the formal handover of power to the majority in Francophone Africa in 1960, French relations with the continent were pursued not by the foreign ministry, but through complex networks (known in French as réseaux) of state and non-state actors. At the heart of these réseaux was the French Presidential Palace, where a dedicated African cell (cellule africaine), led by Foccart, advised the president on African affairs and conducted covert operations in Africa. Private French companies as well as private and public interests in Francophone Africa also played an important role in this opaque network, which is often described as la Franç-afrique. This system, in turn, enabled France to continue to extract profit and exert considerable influence over its former African colonies.

There was extensive overlap between the Franco-African réseaux and the illegal French support given to white Rhodesia after UDI. Many of the private French companies who participated in these networks were also engaged in illegal Rhodesian commerce. Sucres et Denrées (SUCDEN), a Paris-registered company with strong ties to the cellule africaine, operated not only in Francophone Africa, but also in Rhodesia, purchasing considerable quantities of Rhodesian sugar throughout the UDI period. Another striking example of a company close to the heart of French African policy is the airline Union des Transports Aériens (UTA), which participated in Rhodesian affairs. Although UTA suspended its commercial flights to Rhodesia in 1966, the airline maintained offices in Salisbury and Bulawayo (Rhodesia's second city) and was at the forefront of various initiatives to promote Rhodesian trade and tourism after UDI. There were, therefore, various private French companies, that not only had links to the apparatus through which French African policy was conducted, but also participated in illegal Rhodesian trade. This, alongside the notoriously blurred lines between French state and non-state action in Africa, makes it possible to suggest state complicity in French sanctions busting in Rhodesia.

Damning evidence concerning the existence of relations between some key members of the cellule africaine and high-ranking white Rhodesians strengthens this argument. These contacts can be traced back to the early 1960s, when Jean Mauricheau-Beaupré, Foccart's principal deputy in Brazzaville, along with Daniel Richon, UTA's director of external affairs, who frequently acted on behalf of the African cell, attempted to form an organisation comprised of African leaders friendly to France and white rulers of southern Africa, to oppose Anglophone dominance of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), ahead of its first summit in Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital, in May 1963.

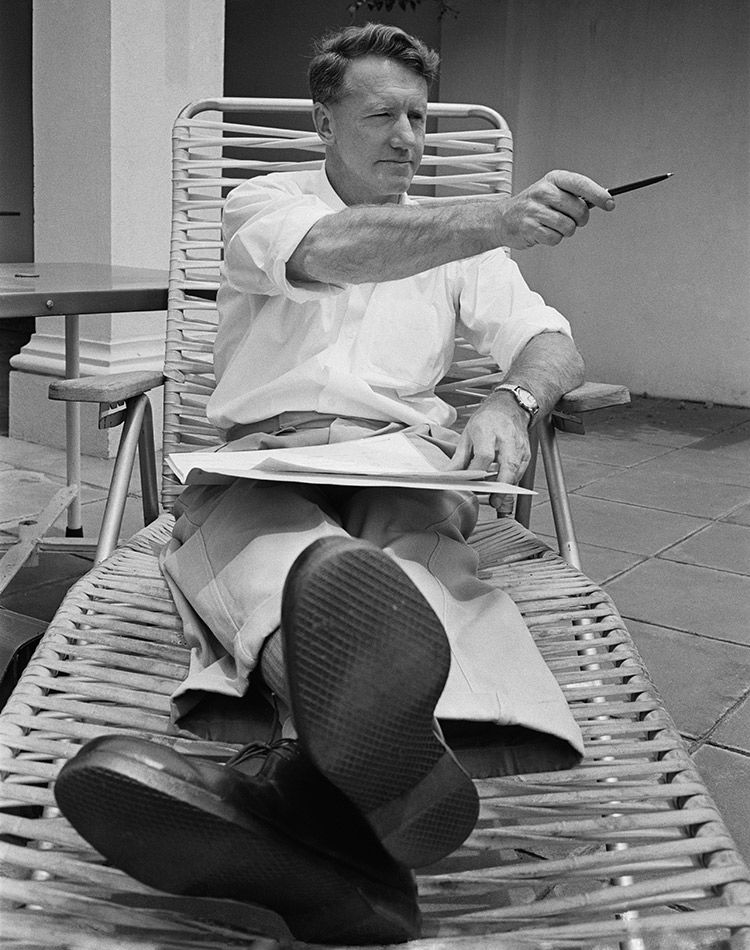

Ian Smith at home in the Rhodesian capital, Salisbury, November 1964. Reg Lancaster / Getty Images

Ian Smith at home in the Rhodesian capital, Salisbury, November 1964. Reg Lancaster / Getty Images

Although this group never fully materialised, it was important in establishing a pattern for covert relations between key players in the Franco-African réseaux and the settler government in Salisbury, permitting Franco-Rhodesian contacts to continue, in secret, after UDI. Mauricheau-Beaupré, for example, met with van der Byl in Paris on at least two occasions that are documented, in 1969 and 1971, and may also have corresponded directly with Smith. Another of Foccart's agents, Philip Létteron, maintained direct personal contact with van der Byl, as well as Geoffrey Follows, a long-serving adviser to the Rhodesian government. In addition, Pierre de la Houssaye, an informant from the Service de Documentation Extérieure et de Contre-Espionnage (SDECE) – France's external intelligence agency – met members of Rhodesia's white settler government, including on a trip to Salisbury in 1970.

These covert channels served an important purpose in facilitating illegal Franco-Rhodesian trade after UDI. French purchases of Rhodesian tobacco, for example, were made possible largely through the existence of a Rhodesian Information Office in Paris. The origins of this office can be traced back to contacts between members of the cellule africaine and certain Rhodesian representatives. Rhodesian sources claim that authorisation to establish a commercial representation in the French capital was given during a meeting between Létteron and van der Byl in Paris in 1966. A similar series of events appears in a SDECE report from 1970. Although this has not so far been verified by archival evidence, the French investigative journalist, Pierre Péan, also asserted in his 1983 study of Affaires Africaines that, until its closure in 1977, the bureau had the support of the Renseignements Généraux (the intelligence service of the French police) and the SDECE. Rhodesian sanctions busting by French individuals and groups appears to have been contingent, therefore, upon the relations that existed between key protagonists of France's African policy and high-ranking Rhodesian settlers.

Furthermore, the extension of Franco-African networks to southern Africa enabled the establishment of commercial relations between Gabon, a former French colony in Equatorial Africa, and Rhodesia. In the late 1960s Mauricheau-Beaupré, Letteron and de la Houssaye introduced the rulers of white Rhodesia to their best Francophone African 'friends', namely Félix Houphouet-Boigny, President of the Ivory Coast (1960-94) and Omar Bongo, President of Gabon (1967-2009), and promoted Gabon as a potential market for Rhodesian beef. In turn, this endorsement led to the development of an enduring trade enterprise, involving the French state and private individuals and groups, Francophone Africans and white settlers, whereby Rhodesian beef was flown into the Gabonese capital of Libreville, before being re-exported to various European capitals, including Amsterdam and Athens. This trade was maintained throughout the UDI period, providing the Rhodesian regime with access to much-needed foreign currency reserves and thus contributing considerably to its survival until 1979. Its significance is attested to in the autobiography of Ken Flower, head of Rhodesia's Central Intelligence Agency, published in 1989, in which he claimed that this venture 'contributed more than any other single factor to the defeat of economic sanctions' in Rhodesia.

It is apparent, therefore, that certain actors linked to the French state, and more specifically those involved in the parallel official mechanisms through which French policy in Africa was conducted after 1960, actively participated in Rhodesian affairs throughout the 14-year period of UDI. The impact of this French involvement was considerable, providing the white Rhodesians and their government with an important economic lifeline at a time of British and international sanctions. Although not the sole external power willing to breach the trade embargo, French support for white Rhodesia was unique due to its intricate entwinement with the networks that formed the basis for France's wider efforts to retain a privileged position on the African continent in the post-independence era.

***

French involvement in Rhodesia stands apart in another way, due to the particular psychological consequences that it had on Rhodesia's white population. As has been noted, at all levels of Rhodesian society, France was seen as an ally and a potential formal backer of white rule in southern Africa. Although official French diplomatic support for Smith's government was never accorded – and it is highly unlikely that this possibility was ever seriously contemplated by France – the fact that such perceptions could exist in the minds of many white Rhodesians underlines the importance that should be accorded to the moral backing Rhodesia received from France, even if this support was sometimes little more than a figment of the Rhodesian imagination. Moreover, the memory of French support outlasted Rhodesia itself, as can be seen by references to it in various memoirs written by former Rhodesian settlers. In Alexandra Fuller's account of her childhood in Rhodesia, Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight (2002), for example, there is a description of being driven around the country in an 'avocado-green Peugeot'. Similarly, Peter Godwin's Mukiwa: A White Boy in Africa (1997) makes reference to the RhAF's use of 'an Allouette helicopter, made in France'. French assistance, both real and imagined, made a lasting imprint on the Rhodesian psyche.

French support for white Rhodesia – physical and psychological, direct and indirect – contributed to Rhodesia's commitment to maintaining white rule in southern Africa. This, in turn, prolonged the settler rebellion against Britain and delayed Zimbabwean independence until 1980. Thus, this episode brings to light a previously unknown dimension of the history of the end of the British Empire, whereby French and Francophone actors crossed national and imperial boundaries to influence the decolonisation process in Anglophone Africa. Beyond the 'secret archives', there exists a much wider history of the British Empire, still in the process of being uncovered by historians.

Moreover, French involvement in Rhodesia was closely bound up with the particular way in which France decolonised its own African empire and the subsequent form of post-colonial Franco-African relations, which enabled the maintenance of ties between certain actors from France, Francophone Africa and Rhodesia. By examining French involvement in Rhodesia historians can not only learn about the end of British colonial rule in Africa. We can also gain fresh insight into France's efforts to maintain its position on the African continent in the post-independence period. This tale of French involvement in Rhodesia after UDI is not merely a hitherto unknown dimension in the story of the end of the British Empire. Rather, it is part of a much wider, interconnected web of previously neglected transnational histories, which provide new perspectives on the end of European colonial rule in Africa. It is only by looking beyond individual Empires and crossing national and colonial boundaries that this secret history of decolonisation will fully come to light.

Joanna Warson is a fellow of the Centre for European and International Studies Research at the University of Portsmouth.

No comments: