Details emerge as sex assault claims pile up against California college's sports medicine director

SAN JOSE, Calif. – The sexual abuse allegations against San Jose State University’s former sports medicine director are more severe and wide-ranging than has been publicly known, court filings in the criminal case headed to trial reveal.

Federal prosecutors charged Scott Shaw in March 2022 with violating the civil rights of four female athletes at the California college by sexually assaulting them during physical therapy sessions from 2017 to 2020.

Those four women – and at least two dozen others spanning more than a decade – said Shaw touched their breasts, buttocks and pelvic regions, often beneath their undergarments, when they went to him seeking treatment for other areas of their bodies. A judge overseeing the criminal case against Shaw will decide how many of them she will allow to testify against him at his trial.

Some of those women described inappropriate touching by Shaw that went even further, court records show:

* A volleyball player said Shaw touched in and around her vagina with his fingers on numerous occasions in 2007 when she sought treatment for shoulder and hip injuries.

* A softball player said Shaw instructed her to lie down on the floor to treat her pulled hamstring, then got on one knee and positioned himself so that their groins touched. As he stretched her, she said, she felt his penis get erect, and she ended the session.

* An employee who worked at SJSU from 2005 to 2009 said Shaw groped her breasts twice when she sought treatment for a shoulder injury, including reaching inside her bra while she was sitting at her desk. She is the first non-athlete to publicly accuse Shaw.

* A soccer player with a knee injury said Shaw moved his hand up the inside of her thigh until his hand was touching her vagina. As a result, she said she quit the team, lost her scholarship and never finished college.

Several of the women said Shaw scoffed and made condescending remarks when they questioned his “techniques,” reminding them he was a trained professional. Many of them said Shaw told them he was performing “pressure-point” or “trigger-point” therapy, relieving pain in one area of the body by putting pressure on another.

Investigation:San Jose State reinvestigates claims athletic trainer inappropriately touched swimmers

The women’s accounts of Shaw’s conduct are “very similar” to those of the hundreds of women and girls sexually abused by Larry Nassar, the former sports medicine physician now serving a life in prison sentence, said Danielle Moore, co-founder of the nonprofit The Army of Survivors.

Moore, a gymnast treated by Nassar while in high school, said she specifically recalled him referring to “trigger points” and “pressure points.” The power dynamics are almost identical in Nassar’s and Shaw’s cases, she said, as young athletes relied on their expertise for clearance to return to playing their sports after injuries. Predators, she added, “find a way to have access to their desired victims.”

“They used their medical knowledge and training and authority as a tool, really, to cover up and silence these athletes and make the athlete kind of feel like they don’t understand what’s going on,” Moore said. “Within the Shaw and Nassar case, they were surrounded, or made themselves be surrounded, by their intended victims.”

Who can testify at Shaw’s trial?

During a two-day hearing Thursday and Friday at the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, prosecutors and Shaw’s defense attorneys argued whether the accounts of those women and a dozen others – 16 in total – should be admissible as evidence in the trial against Shaw, which is scheduled for June.

Prosecutors did not charge Shaw in those women’s cases because their alleged assaults occurred long enough ago that the five-year statute of limitations for the federal civil rights charges has expired.

Judge Beth Labson Freeman sided with prosecutors in all but one case, ruling that 15 women can take the witness stand in Shaw's trial because their descriptions were so similar to those behind the charges facing Shaw. Freeman excluded the testimony of Shaw’s former subordinate, saying the circumstances of her alleged assault differed significantly from the others because she was an employee, not an athlete.

“I don’t want to minimize anyone’s experience or trauma, but these stories just get worse and worse,” said Linzy Warkentin, a former San Jose State swimmer who has accused Shaw of abusing her more than a decade ago. “Those stories need to be heard, and I’m so thankful and relieved the judge has deemed them permissible.”

Prosecutors had argued that the women’s accounts should be admitted because they show that Shaw’s assaults followed the same pattern of behavior over 14 years. For each accuser, the government argued in court filings, Shaw used her need for physical therapy as a pretext to touch her and abused the “disparate power dynamic to act with impunity.”

Their testimony will help establish Shaw's “willful intent” and help the jury understand why some of his accusers continued seeing him for treatment after their assaults, in some cases dozens more times, prosecutors argued. Their testimony also is necessary to understand how Shaw’s conduct came to light and to corroborate one another's accounts, because prosecutors said his victims are the only direct witnesses to his conduct.

What’s the 'magic number’?

Shaw’s attorneys argued the women’s statements should be excluded from evidence mainly because a significant amount of time – six to 13 years – passed between their alleged incidents and the incidents for which Shaw is charged. In addition, they argued that the more “inflammatory” accounts – that Shaw directly touched athletes’ vaginas and pressed his erect penis against one of them – should be excluded because they differ substantially from his charged conduct.

Freeman disagreed. She acknowledged the sexual contact described in those cases was more serious but said it was “quite similar” to the charged conduct, along the same continuum. The circumstances of the alleged assaults, she said, as well as the location and trainer-athlete power dynamic were also the same.

The two sides will now argue on what Freeman called the “magic number” of those athletes who can testify, in addition to the four with whom Shaw is charged with sexually assaulting – enough for prosecutors to be able to make their case, but no so many as to create a “piling-on” effect that could improperly influence the jury, Freeman said.

The prosecution wants to call up to 11, Assistant U.S. Attorney Michael Pitman said in the hearing. Jeremy Blank, one of Shaw’s defense attorneys, advocated for no more than four.

What about other experts?

Shaw’s attorneys also moved to disqualify the prosecution’s two expert witnesses, physicians James Borchers and Cindy Chang, saying their opinions improperly repeated the victims’ testimony and were speculative and unreliable.

Their reviews of the evidence concluded Shaw’s treatments served little legitimate medical purpose and fell “well outside” standard practices. They also determined Shaw lacked proper training for massaging intimate areas of the athletes’ bodies and failed to properly document his treatments, obtain informed consent, apply proper draping, use a chaperone and wear gloves.

Freeman said Borchers and Chang would not be allowed to testify about the victims’ state of mind but declined to prohibit them from taking the witness stand, saying there was “nothing unusual about this kind of testimony.”

Shaw’s attorneys also moved to introduce their own expert witness, Brett DeGooyer, a doctor of osteopathic medicine, who they said will testify that valid reasons exist for touching athletes’ breasts, buttocks and pelvic areas during therapy treatments. Prosecutors did not object.

What’s the backstory?

The allegations against Shaw span 14 years, from when he began at San Jose State as an athletic trainer in 2006 through 2020, the year he resigned.

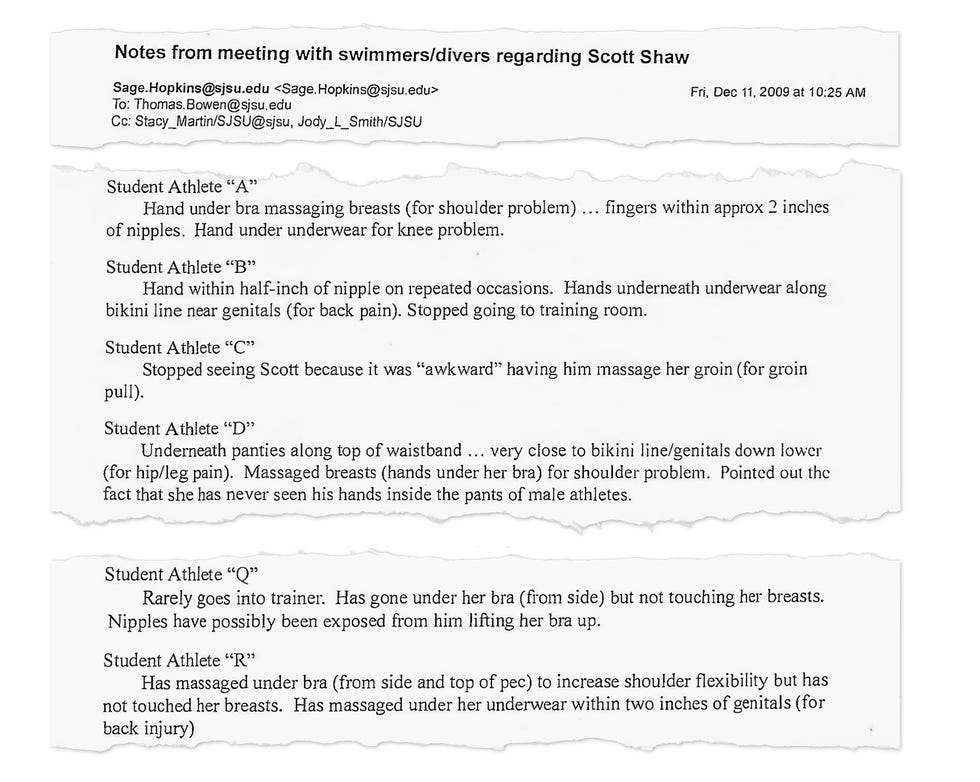

Three years into his tenure, 17 members of the women's swimming and diving team told their coach that Shaw had touched them inappropriately in sensitive areas.

The school launched a human resources investigation that cleared Shaw of wrongdoing. Shaw stayed in his position for another decade, during which time prosecutors say he continued to touch female athletes inappropriately.

Believing the internal investigation was flawed, the swim coach, Sage Hopkins, repeatedly reported the allegations to San Jose State administrators, campus police, the NCAA, the Mountain West Conference and other entities. In January 2020, the school hired an outside law firm to conduct a new investigation.

A year later, the firm’s investigation concluded Shaw’s treatments – conducted under the guise of “trigger-point” or “pressure-point” therapy – lacked medical basis, ignored proper protocols and violated CSU sexual harassment policies.

A separate investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division found San Jose State violated Title IX for more than a decade by failing to adequately respond to the allegations. A subsequent internal review found school officials and campus police failed to sufficiently investigate the allegations in 2009-10.

No comments: