1837 Canada Gives Black Citizens Right To Vote, Though Tumultuously

The path to equal voting rights in Canada is a long and winding road. While Europeans have inhabited the land since the 1400s, the actual origin of its history with voting unsurprisingly begins with the First Nations people, starting all the way back in the 1200s. The Iroquois Confederacy, composed of the Five Nations of Onondaga, Mohawk, Cayuga, Oneida and Seneca, were some of the first people who participated in a voting system we would now identify as democratic. They met in longhouses to settle their respective differences and joined a Grand Council of Chiefs, which decided how the territory would be governed. Both men and women were allowed to have their say, but much changed when European influences took hold over their homeland.

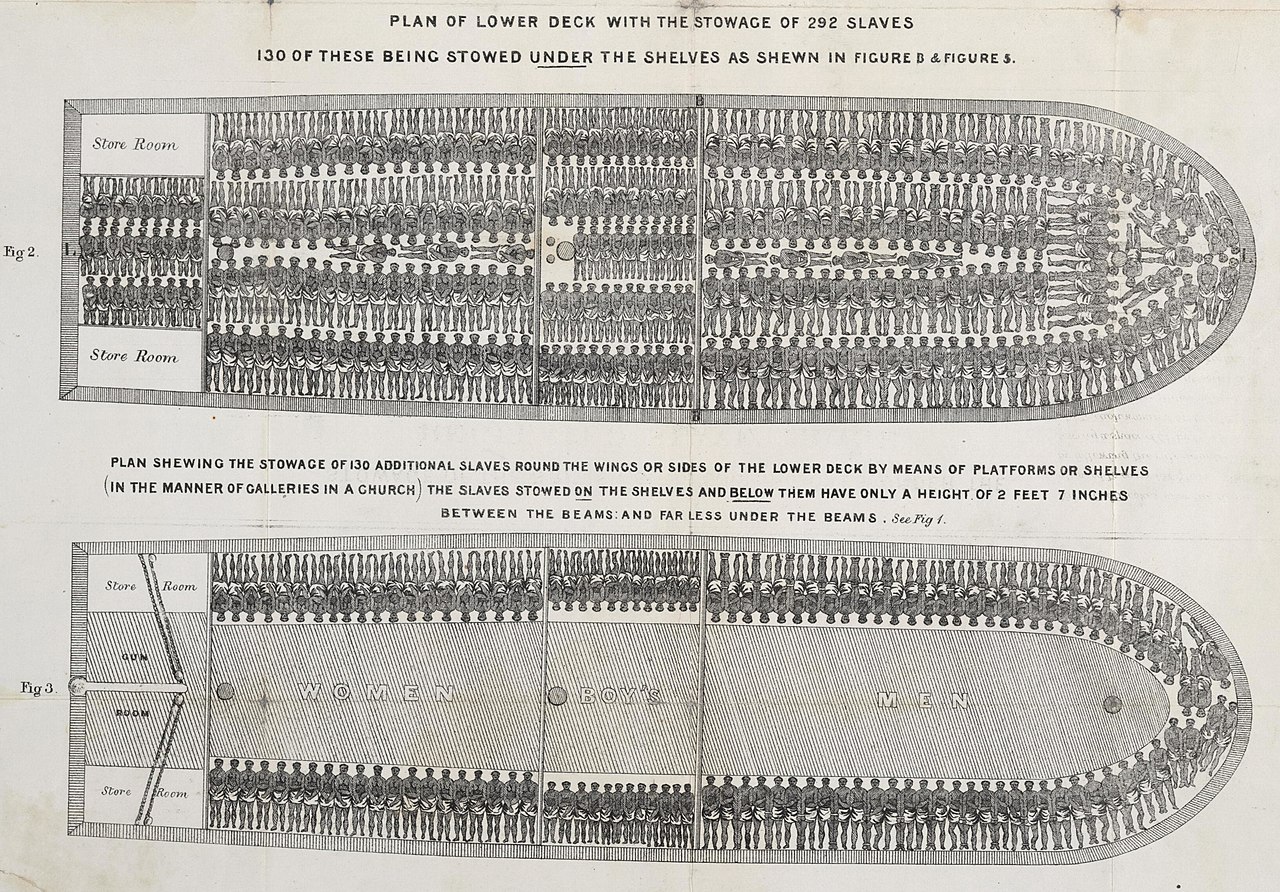

Stowage of a British slave ship, Brookes (1788). (Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons)

The first Europeans who arrived in Canada were probably the Vikings around the year 1000 C.E., but colonization didn't really begin until the late 1400s, when Italian explorer John Cabot landed on the shores of what would aptly later be named Newfoundland. Many colonizing powers, such as France, England, Spain, and Portugal, claimed different regions of Canada over the next centuries, but Canada was firmly under English control by 1763. During this time, voting was reserved in areas like Nova Scotia for predominantly white Protestant men who had enough property to pay taxes. As you can imagine, that left a lot of people with no political voice whatsoever.

As with most colonies, slavery was an all-too-common institution, oppressing both the Indigenous populations and Africans brought over via the transatlantic slave trade. During this era, black slaves were considered "chattel property" under British law, which meant they not only had no rights but were not legally people at all. Infamously in the trial of the Zong, a British slave ship threw over 200 chained people into the Atlantic Ocean after they ran low on rations and then had the gall to ask for reimbursement from their insurance company for their "property." Amazingly, the British court ruled in favor of the ship, but the case awakened many to the evils of the trade slave, kicking off the abolition movement which eventually led Britain to outlaw slavery altogether in 1833.

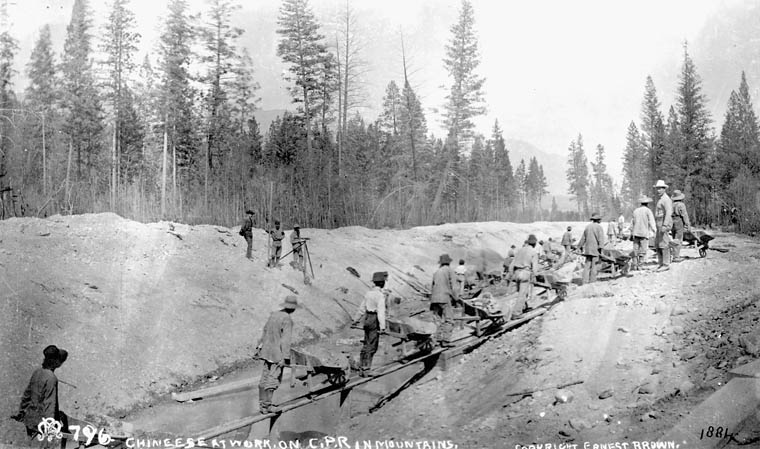

Chinese laborers working on the Canadian Pacific Railway. (Library and Archives/Bibliothèque et Archives Canada/Wikimedia Commons)

Following the abolition of slavery in the English-controlled colonies, former slaves were suddenly granted rights as British subjects. That meant black men should have been allowed to vote, but the requirement of property ownership was still in effect, and freed slaves experienced unique roadblocks to such status. Even if they did manage to acquire property, the difficulty of traveling to the scarce and very often faraway polling locations meant the working class had to take time off work to vote, in addition to countless cultural and "local conventions [that] prevented black persons from voting." It took until 1920 for Canadian citizens to gain the right to vote regardless of taxable property.

As difficult as it was for black Canadians to vote, it was even harder for Asian citizens, thanks to several laws which barred people of Asian descent from voting throughout the 1800s. Anti-Asian racism flourished in Canada following the mass immigration of Chinese people fleeing unrest in conflicts like the Opium Wars and seeking fortune in the Americas, especially during the Gold Rush of the 1850s, resulting in such laws. In 1885, the federal government specifically targeted Chinese-Canadians by revoking their right to vote in the Electoral Franchise Act. In 1895, Japanese-Canadians were likewise banned from casting their ballot.

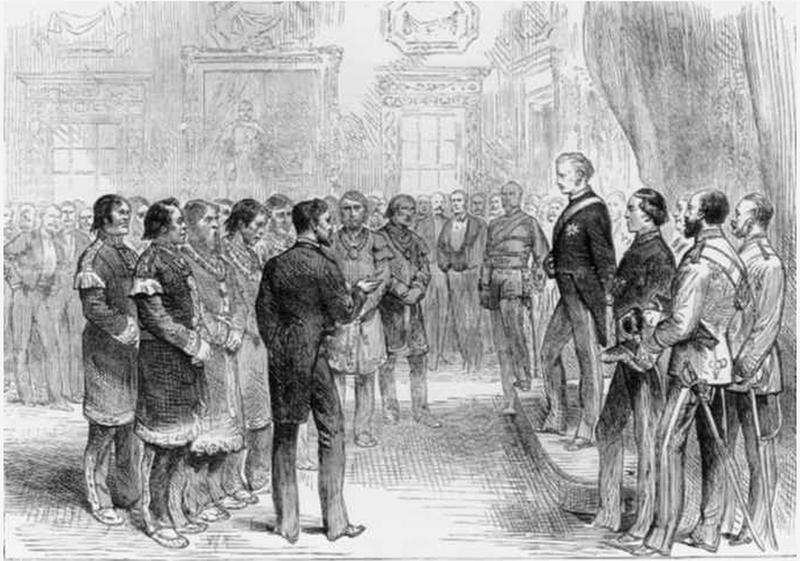

Mi'kmaq Grand Chief Jacques-Pierre Peminuit Paul (3rd from left with beard) meets Governor General of Canada, Marquess of Lorne, Red Chamber, Province House, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1879. (Unknown author/Wikimedia Commons)

Thankfully, in 1948, Canada passed the federal Elections Act, which took race out of the equation entirely ... that is, of course, except for members of the First Nations. First Nation peoples held certain unique rights under Canadian law, won through various treaties over the decades, that allowed them to live on reservations, retaining sole control over resources and the right to self-govern.

However, as of 1857, if a First Nations citizen wanted to vote in any federal election, they had to give up their status and conform to larger Canadian society, specifically the assimilation guidelines laid out in laws like An Act to Encourage the Gradual Civilization of the Indian Tribes. (They really did not pull any punches with these act names.) Understandably, many refused to denounce their heritage, and that year a whopping one man decided to give up his status to participate in the election. After World War I, the government allowed those who had served to vote without losing their status, but it took until 1960 to extend this freedom to all Indigenous Canadians.

No comments: