Birmingham Church Bombing: The 16th Street Baptist Church Killings Of Four Black Children

On Sunday, September 15, 1963, the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama was destroyed by members of the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. This deadly bombing killed four black children, injured more than 20 other parishioners, and ripped through the Civil Rights movement like a bolt of lightning. The perpetrators went unpunished for decades, but thanks to the vigilance of the FBI, three of the four members of the group who took the lives of four innocent girls were put away for good.

A Powder Keg In Birmingham

As a hot spot of racial tension in the already racially tense South of the '50s and '60s, Birmingham was ground zero of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s anti-racism work. In his famous "Letter From A Birmingham Jail" in April 1963, King wrote of the city:

Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced grossly unjust treatment in the courts. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the nation. These are the hard, brutal facts of the case. On the basis of these conditions, Negro leaders sought to negotiate with the city fathers. But the latter consistently refused to engage in good faith negotiation.

Clearly, the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing wasn't the first time a rudimentary explosive device was used to maim and and murder black churchgoers. In fact, it was such a common occurrence in Birmingham, one of the last vestiges of unrestrained white supremacy in the South, that the city earned the nickname "Bombingham." Wherever a Civil Rights meeting or protest was taking place, it was a safe bet that the Klan, who had become increasingly violent as the area's Civil Rights leaders became increasingly vocal, would call in a bomb threat, especially at the 16th Street Baptist Church.

(CNN)

The 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing

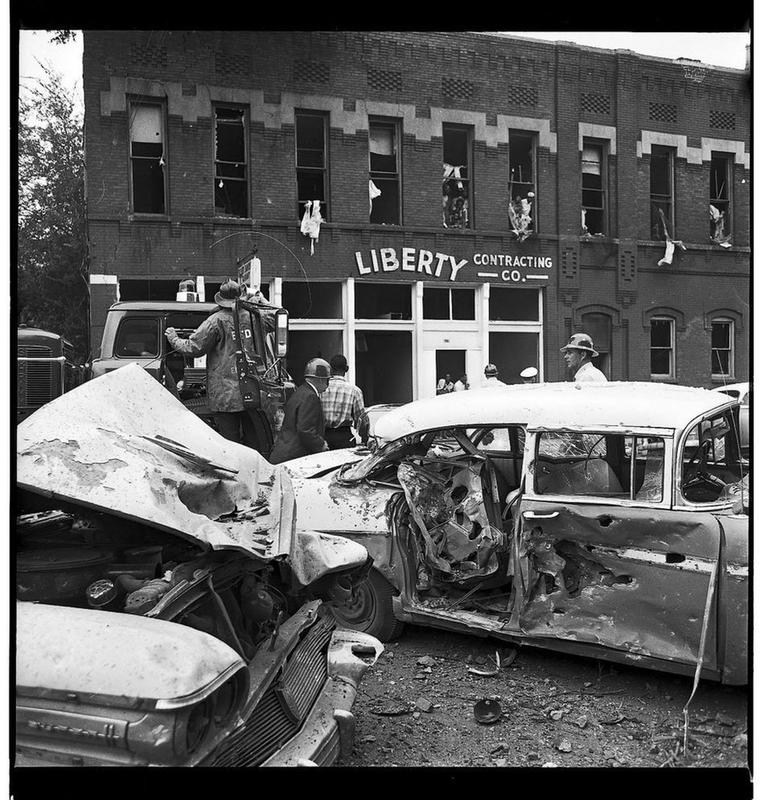

The parish of the 16th Street Baptist Church was out in full effect on September 15, 1963. Like many people across the city, they were just trying to go to church, but at 10:22 a.m., four dynamite sticks attached to a timer detonated on the east side of the church. Its walls imploded, and shrapnel flew across the area, spraying people who were moving from Sunday school classes to the 11 a.m. service.

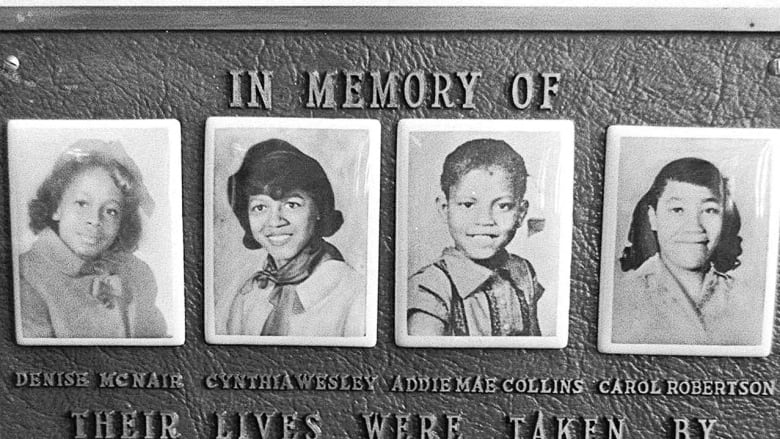

The sound was deafening, and people ran for cover in all directions as ash and plaster rained down and smoke filled what was left of the building. The force of the blast was so massive that it destroyed cars in the parking lot and blew out windows in homes down the street. At the end of the day, some 22 people were injured, and four girls—14-year-olds Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, and Carole Robertson and 11-year-old Denise McNair—were dead. Reverend John Cross later noted that the girls were found "stacked on top of each other, clung together."

(CBC)

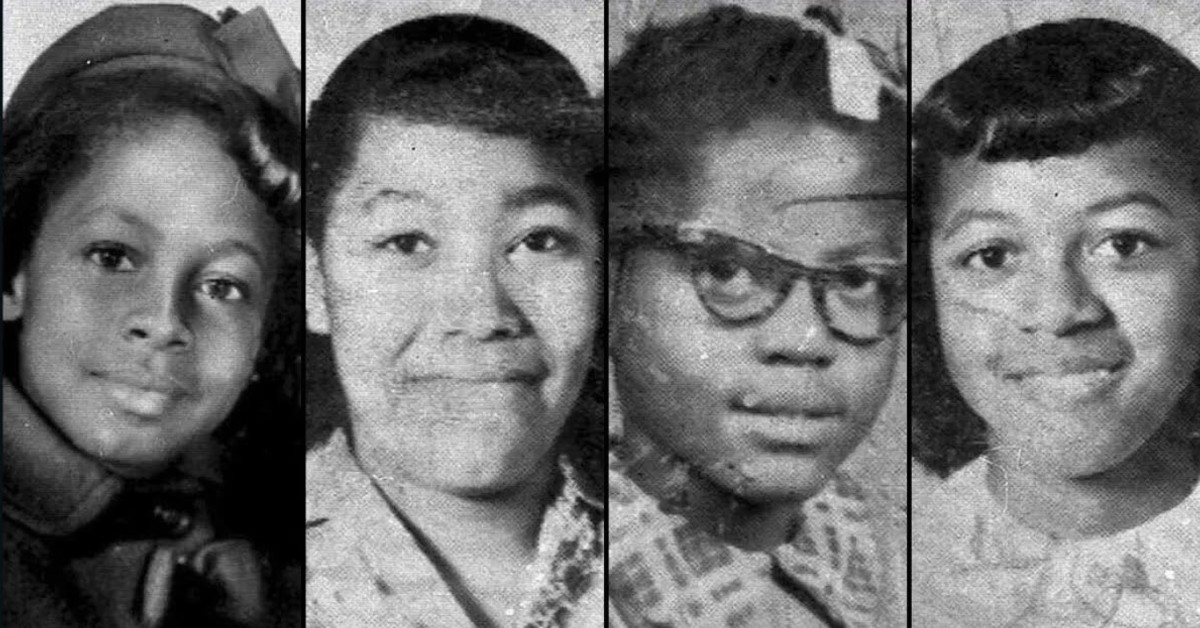

The Victims

In death, the four girls who lost their lives during the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing became symbols of the civil rights movement, but before the explosion, they were just girls. Addie Mae Collins went to church every Sunday with her parents and six siblings, Cynthia Wesley was excited to begin attending Ullman High School, and Carole Robertson was one of Alpha and Alvin Robertson's three children. In 1976, Alpha Robertson gave the Carole Robertson Center for Learning permission to use her daughter's name to help children in Chicago receive after school educational services. Denise McNair, the youngest of the victims, was the daughter of one of the first black members of the Alabama Legislature, Chris McNair. When he passed away at the age of 93 in 2019, his funeral was held at the rebuilt 16th Street Baptist Church.

(Alabama Media Group)

The Aftermath

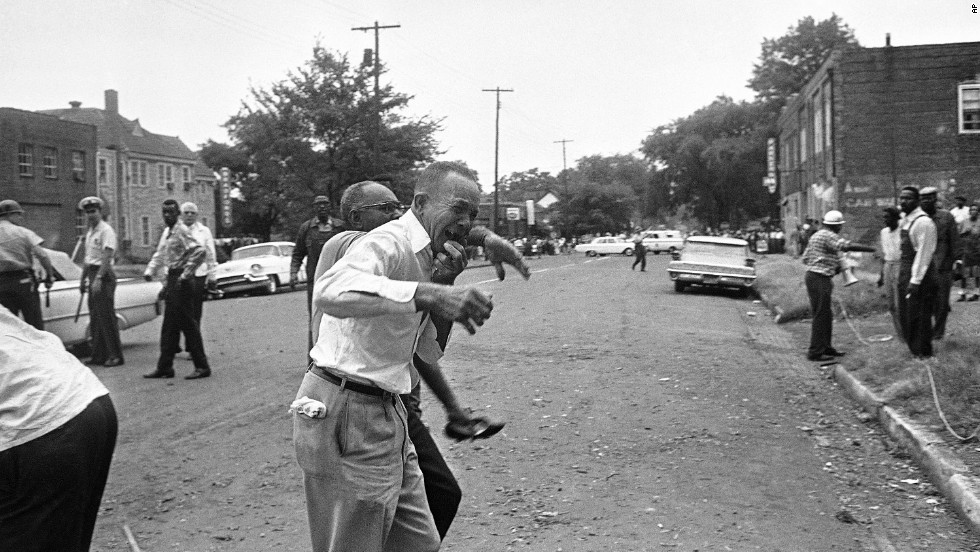

In the days following the bombing, at least 300 members of the state police had to be brought into the city to quell the violence that raged between black and white youth. Multiple businesses were firebombed, cars were smashed with rocks, and riots broke out, leaving the city in chaos. Two more young black people, Johnny Robinson and Virgil Ware, were shot to death seven hours after the bombing.

The FBI came to town to investigate the bombing while the city of Birmingham offered a $52,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of the bombers, but when Governor George Wallace put up an additional $5,000, Martin Luther King, Jr. accused him of hypocrisy. His letter to the governor read in part:

The blood of four little children ... is on your hands. Your irresponsible and misguided actions have created in Birmingham and Alabama the atmosphere that has induced continued violence and now murder.

The event became a focal point of the Civil Rights movement and eventually led to Congress's passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but the men responsible for the bombing remained free.

(Pinterest)

Escaping Justice

The FBI quickly zeroed in on the men responsible for the bombing, but maddeningly, they couldn't do anything about it. There was little evidence tying Thomas Blanton, Jr., Herman Cash, Robert Chambliss, and Bobby Cherry—members of a splinter group called the "Cahaba Boys" for whom the KKK simply wasn't extreme enough—to the explosion. Still, on May 13, 1965, all four men were officially identified as the perpetrators, but later that year, J. Edgar Hoover blocked federal prosecutions against the suspects. Three years later, the case was closed, and the files were sealed by Hoover.

(Narratively)

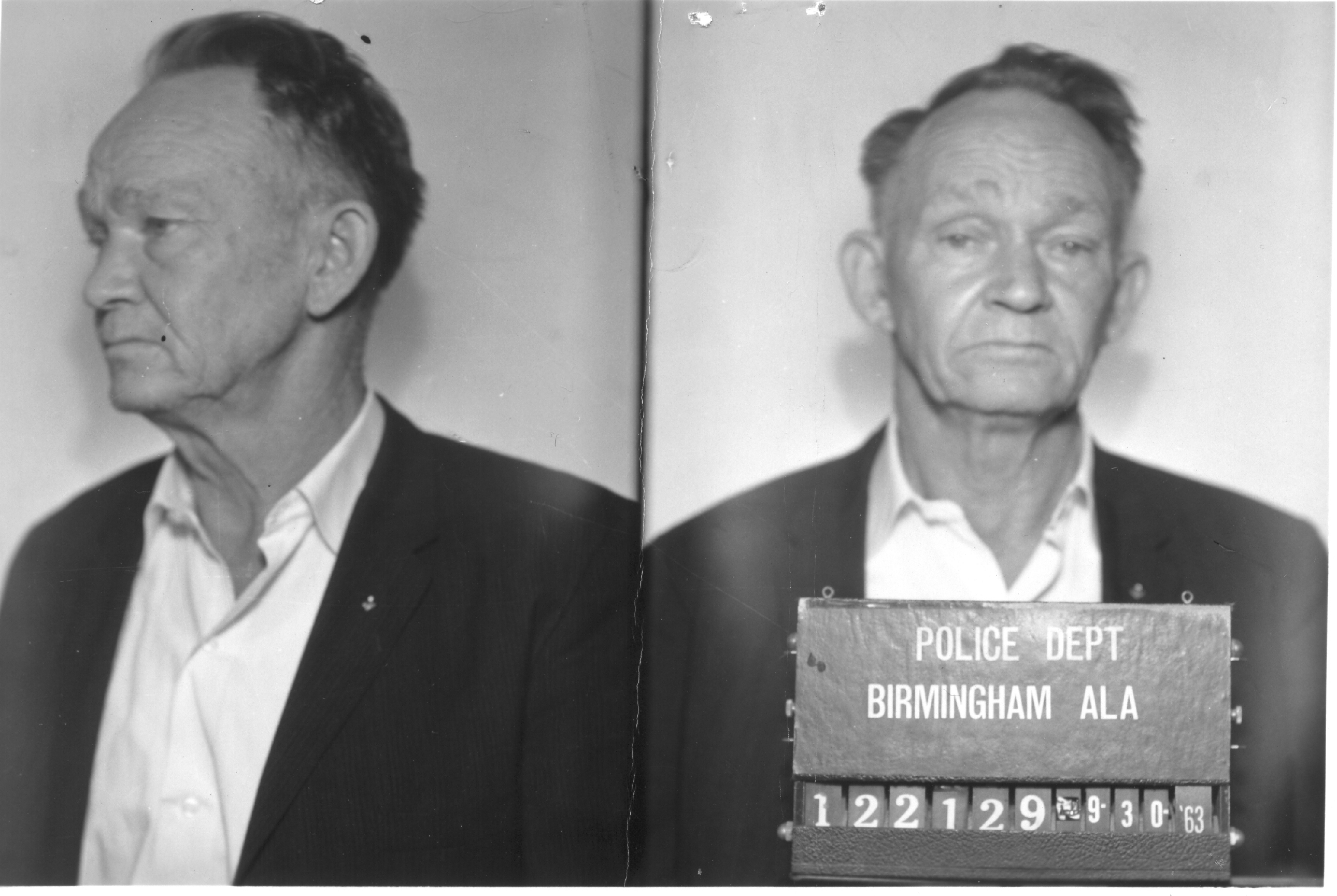

The First Conviction

Throughout the initial investigation, the FBI believed that Robert Chambliss was the ringleader of the group behind the bombing. When William Baxley was elected attorney general of Alabama in January 1971, he lobbied to reopen the case, and through his investigation, he discovered that Chambliss bought the dynamite used in the bomb two weeks before the explosion. Chambliss likely placed it inside the church in the early hours of September 15.

Chambliss was 73 years old when he went on trial in Birmingham for four counts of murder, and on November 18, 1977, he was found guilty of the murder of Denise McNair and sentenced to life in prison. He never admitted to bombing the church, claiming that a man named Gary Thomas Rowe, Jr. was responsible. Chambliss passed away on October 29, 1985 at the age of 81.

(Mercury News)

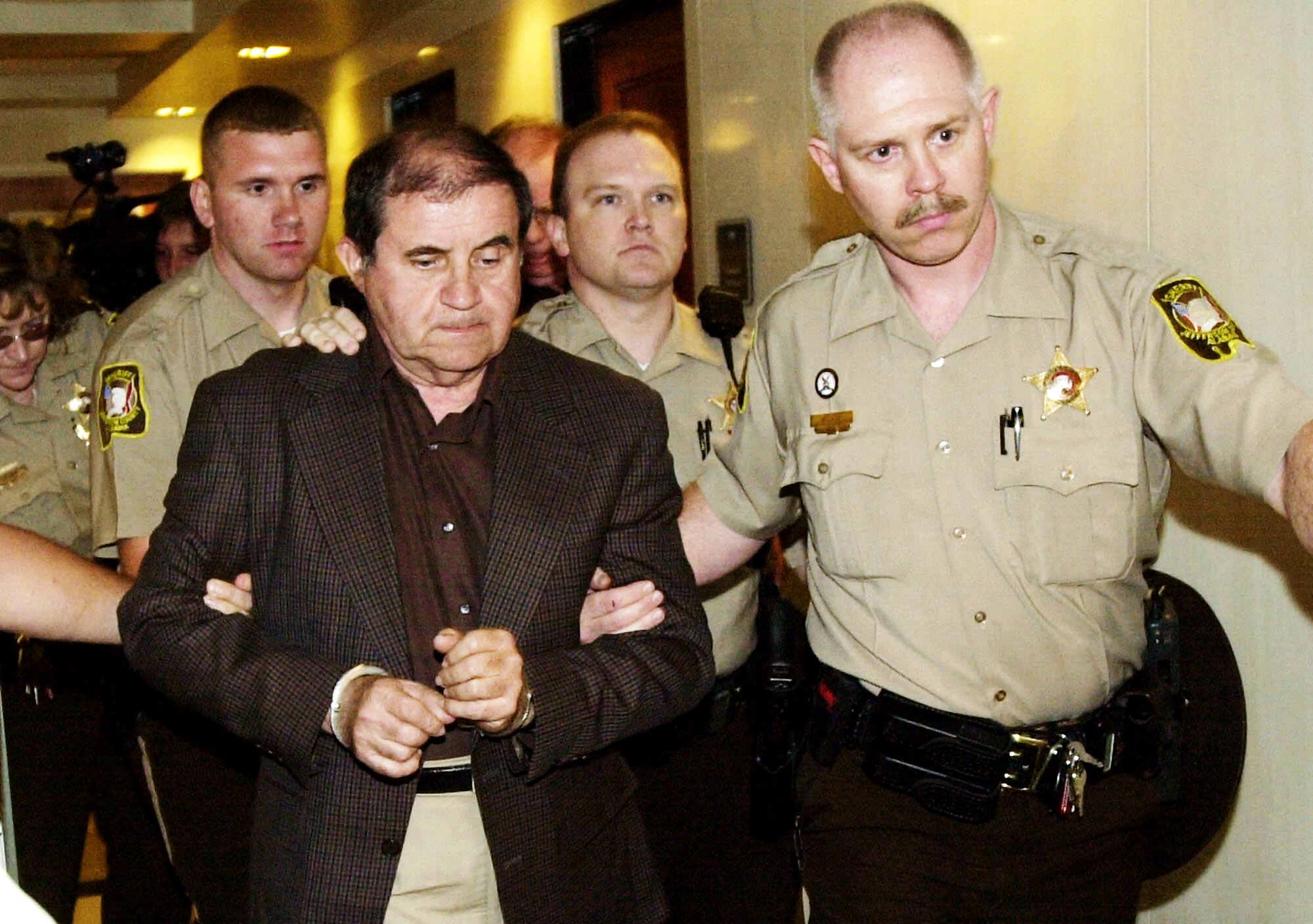

Closing The Book

More than 30 years after the bombing in Birmingham, the FBI reopened their investigation, looping in local and state governments to review all of the evidence collected at the time as well as new evidence that came to light. In 2000, they arrested Thomas Blanton and Bobby Cherry, who were tried on four counts of first-degree murder and four counts of universal malice. (Herman Cash had since passed away.) Their trial was repeatedly postponed due to their age and health, but Cherry and Blanton were both found guilty and died in prison in 2004 and 2020, respectively.

No comments: