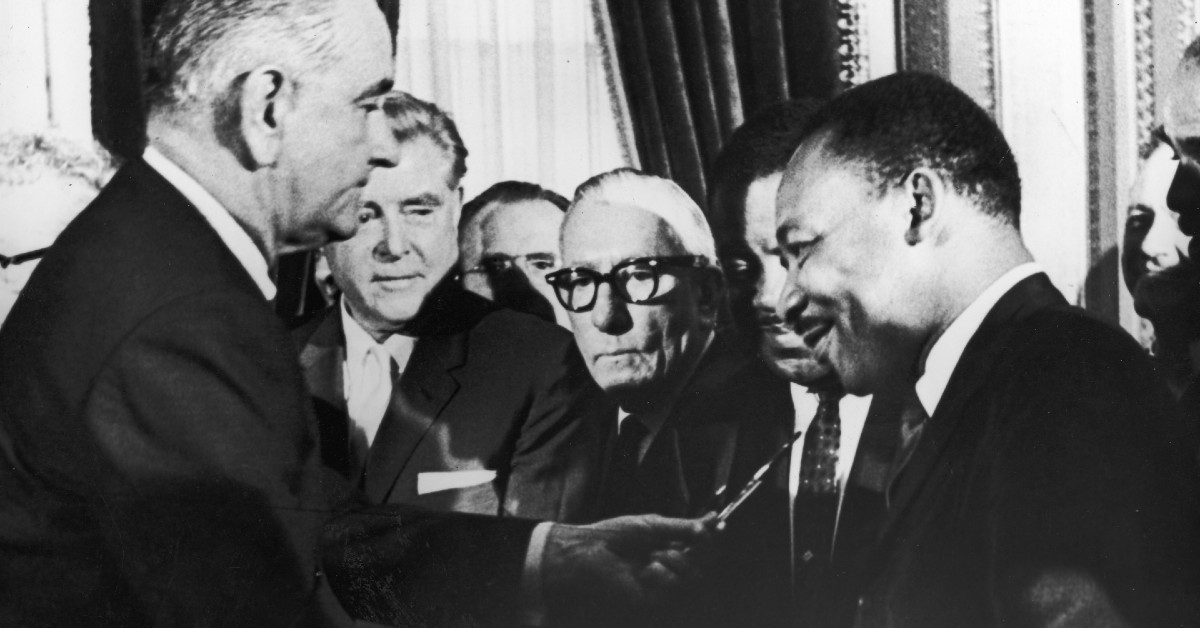

1965: Voting Rights Act Is Signed By Lyndon B. Johnson

U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson hands a pen to Civil Rights leader Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. during the signing of the Voting Rights Act as officials look on behind them, Washington, D.C., August 6, 1965. (Washington Bureau/Getty Images)

The Civil Rights movement was alive and kicking long before Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in following John F. Kennedy's assassination in 1963 and freely elected the following year, but it was Johnson who signed the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The act, which was signed on August 6 of that year, is widely believed to be the most comprehensive Civil Rights law in United States history.

A Review Of Voting In The U.S.

When the United States was founded in 1776, the only people allowed to vote were white, male, land-owning Protestants. The 1790 Naturalization Law modified that mandate to grant free white men the right to vote upon becoming citizens, and the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo of 1848 bestowed U.S. citizenship upon Mexicans living in the land conquered by the United States but required English language reading and writing as a condition of voting. The 14th Amendment, passed in 1868, granted citizenship to former slaves but limited voting privileges only to men. The 15th Amendment declared that individual states couldn't deny voting rights based on race or former condition of servitude, and women were given the right to vote in 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

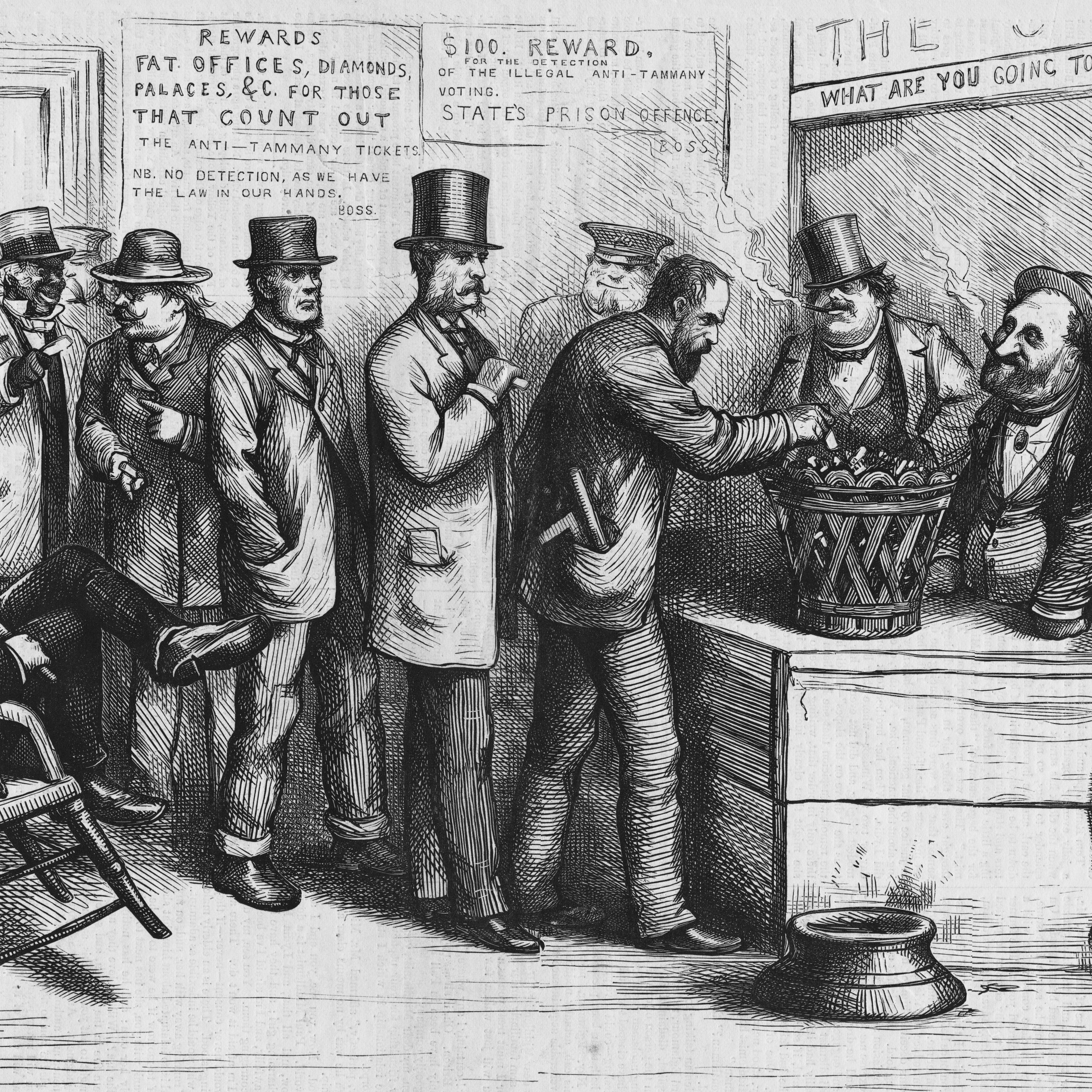

Sneaking Around The Amendments

Despite the lengthy process of closing the gaps in voting laws, however, several states still found ways to get around them. Confusing "literacy" tests, complicated oral exams, strategic placement of polling centers away from public transportation routes, and other convoluted measures prevented even the most educated black citizens from casting their vote.

In addition to these underhanded techniques, many Southern election officials engaged in overt deception and threats of violence to keep black voters away from the ballot boxes. In many cases, when black voters arrived to cast their ballot, they were told they were at the wrong location or arrived a day too late. Some were given an application to fill out and then told they could not vote due to an application error. In some locations, armed officers used force and intimidation to keep black voters from making their voices heard on Election Day. Stories abound about black voters being shot at or beaten with clubs.

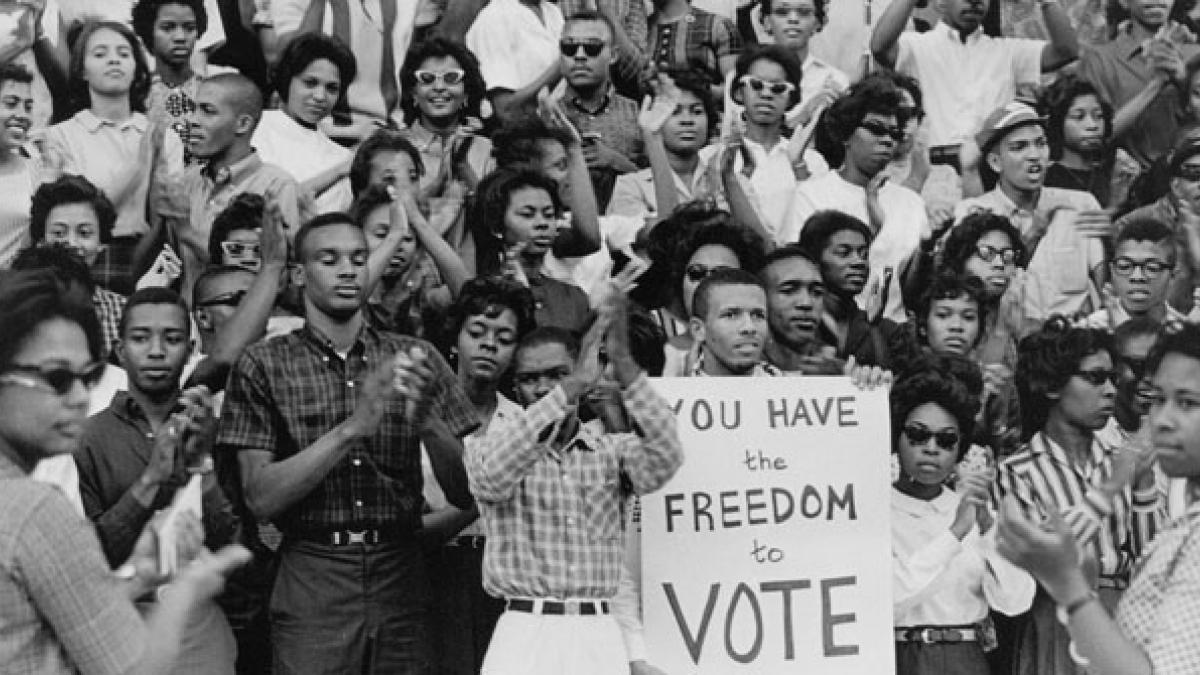

Voting Rights Activism In The Civil Rights Era

As the Civil Rights era picked up steam in the '50s and '60s, activists shined increasingly brighter lights on the obstacles to voting that black residents of the South faced. On March 7, 1965, a group of peaceful protesters at a voting rights march were attacked, beaten, and gassed by Alabama state police troopers in a violent event that was captured on video and broadcast on national news all over the country.

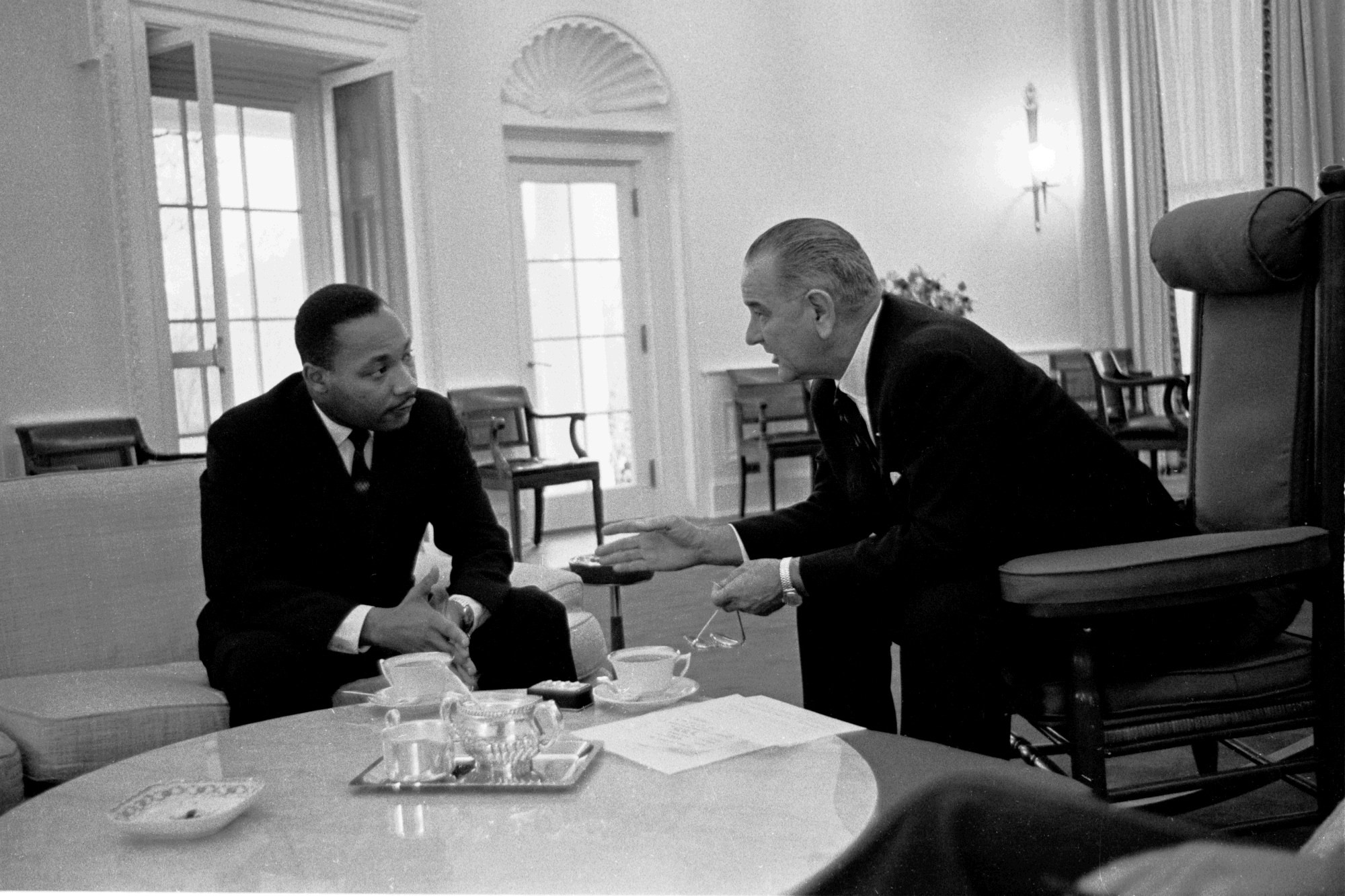

It was a turning point in the voting rights movement. One week later, on March 15, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson delivered a speech about voting rights to a joint session of Congress, calling on them to pass all-encompassing legislation to prevent states from using these tactics.

The Voting Rights Act

On May 26, 1965, the United States Senate passed the Voting Rights Act, which was passed by the House of Representatives on July 9. The act provided federal oversight to areas where less than half of the non-white population was registered to vote and banned literacy tests and poll taxes. At an August 6, 1965 ceremony attended by Martin Luther King, Jr. and several other prominent figures in the Civil Rights movement, President Johnson signed the act into law.

The Aftermath

Although voter intimidation continued, it was clear that many communities in the Deep South suddenly viewed black voters as a force to be reckoned with. The act, which gave black voters legal recourse if they were unjustly turned away from the polls, led to a spike in black votes across the South. In Mississippi, for example, less than 6% of black residents voted in the 1964 election, but nearly 60% did in 1969.

Since 1965, the Voting Rights Act has been amended several times to reflect the changing face of America. One such change included Native American, Alaskan, Asian-American, and Mexican-American voting rights. Another protected the voting rights of non-English-speaking U.S. citizens. Although voter suppression remains a serious issue in some places, the Voting Rights Act is ready for whatever they can throw at it.

No comments: