Orson Welles: Actor, Director, Writer, Legend, And Eventual Magician

(Janus Films)

Reaching the zenith of your career in your twenties has to be maddening. Orson Welles directed Citizen Kane when he was only 25 years old, and even though he never won an Academy Award, he created what's still known as modern filmmaking. We think of him as a legendary filmmaker today, but while Welles was alive, he was regarded as a joke and a has-been. War of the Worlds and Citizen Kane were monumental achievements that he never really topped, not in the eyes of critics at the time, but Welles never stopped dreaming.

Orson Welles, Cheese Head

Born in Kenosha, Wisconsin on May 6, 1915, George Orson Welles grew up in a broken home. His father was an alcoholic who squandered his earnings from his invention of the bicycle lamp, his brother was institutionalized, and his mother died of hepatitis in 1924, just after his ninth birthday. In his youth, Welles was interested in music, but following his mother's death, he gave up this pursuit and embarked upon a chaotic, transient life with his father.

Welles and his father moved from place to place until the young man was enrolled in the Todd Seminary for Boys, where he was encouraged to experiment with art. His first forays into radio took place while attending this school. After his father died, he decided against attending college, instead using his small inheritance to travel through Europe.

Orson Welles, Shakespeare Lover

While traveling through Europe in the 1930s, Welles took his first job in the theater at the Gate Theatre in Dublin after strutting in and claiming to be a Broadway star. Hilton Edwards, the manager of the company, recalled that he didn't believe Welles but appreciated the kid's chutzpah. On October 13, 1931, he appeared in Ashley Dukes's adaptation of Jew Suss as Duke Karl Alexander of Württemberg.

Welles could have continued acting in Europe, but he threw himself into a project called Everybody's Shakespeare, a collection of educational books about the Bard. At the time, Welles was deep in the middle of studying Shakespeare and felt that his own writing would never stand up the most beloved plays of all time. He wrote to friend and former guardian Roger Hill:

I'll be relieved when I can get this off in the mails. The mere presence of Shakespeare's script worries me. What right have I to give credulous and believing innocents an inflection for his mighty lines? Who am I to say that this one is "tender" and this one is said "angrily" and this "with a smile?" There are as many interpretations for characters in Caesar as there are in God's spacious firmament. What nerve I have to pick out one of them and cram it down any child's throat, coloring, perhaps permanently, his whole conception of the play?

Orson Welles, Black Theater Pioneer?

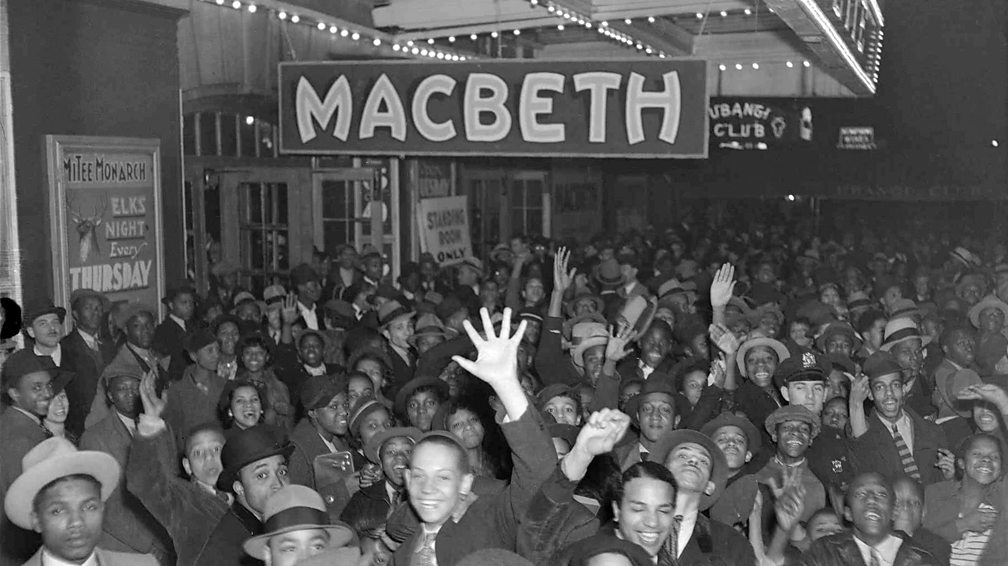

Working as a radio personality, Welles began using his income to fund productions of legitimately groundbreaking plays like an all-black interpretation of Macbeth in which Haitian vodou replaced Scottish witchcraft. In 1936, the performance was hailed as beautifully transgressive and he as a visionary. Welles was only 20 years old at the time. One year after the performance, Welles formed his own repertory company, the Mercury Theater.

Radio Days

By 1937, Orson Welles was one of the busiest creatives on the planet. He was writing, directing, and starring in shows for the Mercury Theater and keeping up with radio commitments that earned him around $2,000 a week. When the Mercury Theater's performances proved successful, Welles decided to combine his two loves. Beginning on July 11, 1938, Welles and his troupe began putting on an hourly radio drama with The Mercury Theater on the Air.

On October 30, 1938, Welles got his first taste of international fame with his radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds. The story, told through a series of news bulletins and a real recording of a symphony for the first half with a more straightforward story in the finale, was so impressively performed that some listeners initially mistook it for a real news broadcast. The key words there are "some" and "initially." The show was groundbreaking, but the story that it plunged America into an actual panic isn't true. Only 2% of 5,000 households even listened to the radio drama, which were pretty good numbers for a broadcast but not for a catastrophe.

The Failure Of Citizen Kane

Thanks to Welles's success with the Mercury Theater, Hollywood started taking notice of the brilliant youngster, but none could persuade him except RKO Radio Pictures President George Schaefer. The man himself offered Welles the opportunity to write, produce, direct, and perform in two motion pictures, with complete creative control and final cut of the product. He couldn't say no, and after a few failed proposals, RKO accepted his pitch for Citizen Kane, a thinly veiled fictionalization of the life of William Randolph Hearst.

The film is the culmination of Welles's genius, drawing on the expertise of cinematographer Gregg Toland and the Mercury Theater players. Hearst was allegedly so freaked out about Citizen Kane that he tried to bribe RKO Pictures to destroy all the negatives of the film. When that didn't work out, he used his newspapers to trash the film, guaranteeing its failure at the box office. The film was shelved after its initial theatrical release, and it took more than a decade for Welles's work to be recognized as visionary.

A Hollywood Circus

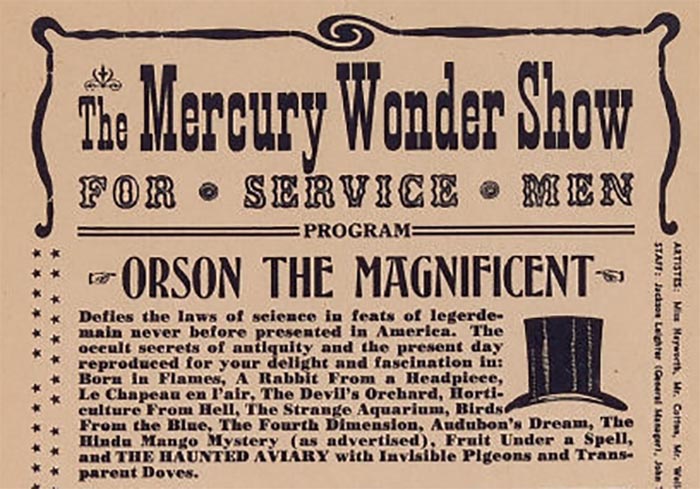

Demoralized by his treatment during Citizen Kane, Welles threw himself into work as a goodwill ambassador to Latin America during World War II while working on films like Journey Into Fear and It’s All True, an unfinished film about the region. Eventually, he moved on from this project to direct and perform in The Mercury Wonder Show—a variety program that was part big-top spectacle, part circus, and part magic show—for the U.S. Armed Forces.

From August 3–September 9, 1943, Welles performed the show in a giant tent at 9000 Cahuenga Boulevard, smack dab in the middle of Hollywood. Servicemen were admitted for free, and after that, tickets cost around $5 for adults, while the Hollywood elite were allowed to purchase tickets for $30 to sit in the "sucker section." Anyone who wanted to spend $50–$100 on the "super sucker" seats situated behind two poles—usually someone like Sam Goldwyn or Jack Warner—ended up as the butt of the jokes in front of the mostly military audience.

Post-War Slump

Welles couldn't serve in the military due to a number of medical problems, so he stuck to performing for the troops live and on the radio until the end of the war. In 1946, he directed The Stranger, a film about a war crimes investigator who tracks a high-ranking Nazi fugitive to a small New England town. This film noir was the only movie of Welles's that was considered a financial success.

Following the release of The Stranger, Welles began working on a series of film, television, and radio projects, with mixed results. He followed his heart back to Shakespeare, and while his adaptations of Macbeth and Othello were critically successful, they weren't box office hits by any means.

Taking whatever acting roles he was offered, Welles funneled all of his money into filming his own productions, ranging from Don Quixote to The Other Side of the Wind to The Merchant of Venice. Throughout the '50s and '60s, he bounced back and forth between Europe and America, acting in films like John Huston's Moby Dick, Joseph McGrath's Casino Royale, and Catch-22 by Mike Nichols.

The "Screw It" Final Years

Throughout the '70s, Welles never stopped appearing in film and television, whether it was onscreen or as an unseen but unmistakable voice. A constant dreamer, Welles never stopped attempting to produce his own work, and he spent the final years of his life perfecting his magic tricks and filming a television special that he never finished. He funded these projects through a series of commercials for Paul Masson wine, a decision that turned him into a laughingstock.

Welles loved illusions more than anything, whether on film, stage, or the radio waves, but he never realized his dream of casting a spell over an audience. Not with his magic act, anyway. He passed away on October 10, 1985 after a heart attack, and his ashes were buried in Ronda, Spain in 1987.

No comments: