A Mining Company Just Blew Up A 46,000-Year-Old Aboriginal Site — And It Was Totally Legal

A mining company destroyed a 46,000-year-old rock shelter that was sacred to Australia’s Indigenous peoples.

A 46,000-year-old cultural site significant to Australia’s indigenous people was destroyed by a mining company expanding its iron ore territory. The destructive act was deliberately done with the permission of the Australian government.

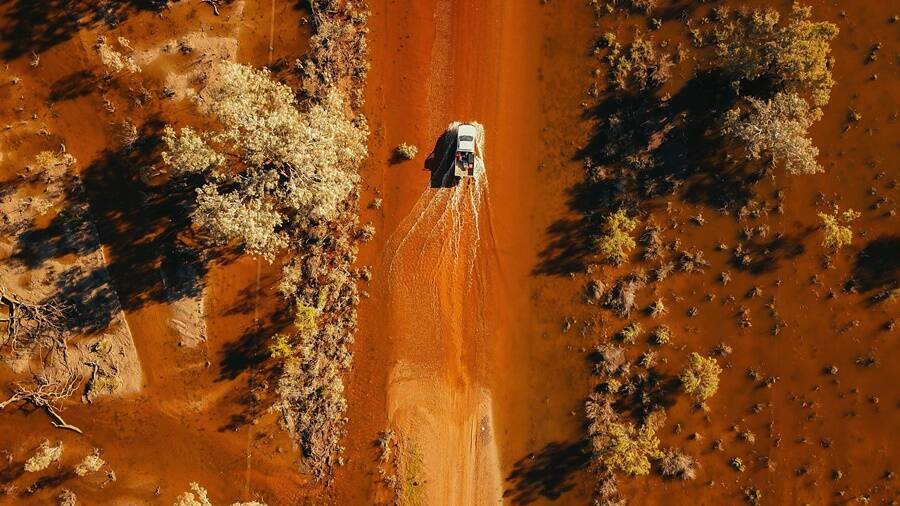

According to the Guardian, the destroyed site was a rock shelter located in Juukan Gorge in Western Australia that had been continuously occupied by the early inhabitants of the territory dating back over 46,000 years.

The cave was one of the oldest in the western Pilbara region and the only inland site with evidence of continual habitation which lasted through the last Ice Age.

“It’s one of the most sacred sites in the Pilbara region…we wanted to have that area protected,” said Burchell Hayes, the director of the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura (PKKP) Aboriginal Corporation which oversees the land.

Reforms to the Aboriginal Heritage Act were postponed due to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.

In addition to its meaning to indigenous people, the site also held great archeological value. Excavations there unearthed a bevy of precious artifacts, including a 4,000-year-old length of plaited human hair. Incredibly, DNA analysis showed the hair belonged to the direct ancestors of the PKKP peoples today.

“It is precious to have something like that plaited hair, found on our country, and then have further testing link it back to the Kurrama people. It’s something to be proud of, but it’s also sad. Its resting place for 4,000 years is no longer there,” Hayes said.

Rio Tinto, the mining company that destroyed the cave, had received permission to demolish the sacred site in 2013. The permission was granted by the Department of Aboriginal Affairs under Western Australia’s outdated Aboriginal Heritage Act which was first established in 1972.

In 2014, an archaeological dig was approved so that researchers could salvage the artifacts inside the rock shelter.

The excavation revealed that the site was actually twice as old as previously estimated and carried a trove of more than 7,000 sacred artifacts, including 40,000-year-old grindstones and thousands of bones from refuse piles which showed changes in wildlife during the prehistoric period.

Archeologist Michael Slack, who led the project, said it was a once-in-a-lifetime discovery.

But the Aboriginal Act law was drafted in favor of mining proponents and did not allow for amendments to consent orders or agreements. On May 24, 2020, the cave was blasted by Rio Tinto to make way for its iron ore mining expansion.

The cave site in Western Australia boasted a trove of precious artifacts that told of the country’s rich history.

Now, the 46,000-year-old enclave no longer exists.

“Now, if this site has been destroyed, then we can tell them stories but we can’t show them photographs or take them out there to stand at the rock shelter and say: this is where your ancestors lived, starting 46,000 years ago,” Hayes said of the sacred site’s demolition.

Rio Tinto first signed a native title agreement with the traditional PKKP owners in 2011, four years before the tribespeople’s native title claim was formally ruled on by the federal court. The company also facilitated the dig in 2014.

Following the new discoveries, the company pushed for its original agreement with the government over the Juukan site to be carried out, even after the Aboriginal Heritage Act was put under review when the Labor administration took over in 2017.

The company stated it was supportive of the proposed reforms but argued that the consent orders that had already been approved should continue.

The final consultation of the bill’s draft was pushed back by Aboriginal Affairs Minister Ken Wyatt due to the coronavirus outbreak this year.

Meanwhile, the loss of a rich source of Australia’s history is mourned by Indigenous advocates and researchers.

“It was the sort of site you do not get very often, you could have worked there for years,” Slack said. “How significant does something have to be, to be valued by wider society?”

Disgusting!

ReplyDelete46,000 years old and was allowed to be destroyed? not likely.

ReplyDeleteDid the article mention that an indigenous company oversees this stuff and took money for permission for this? I guess not.

ReplyDeleteWell that shows they cannot build anything beyond rock dwellings and mud huts like beavers.

ReplyDelete'ab original'

ReplyDeleteso go ahead