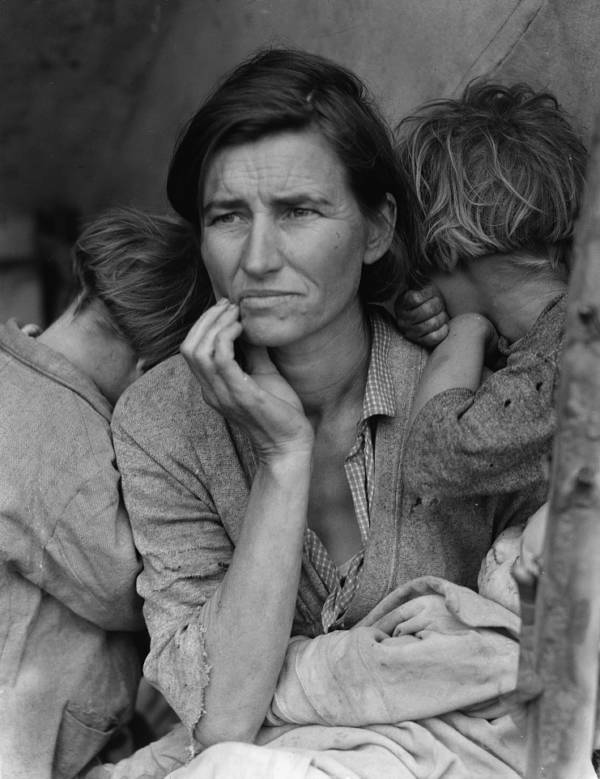

The True Story Of The Iconic “Migrant Mother” Photograph

The "Migrant Mother" photo is iconic — but if the subject had her way, she wouldn't be the face of the Great Depression.

In 1936, a very tired 32-year-old mother of seven named Florence Owens sat down with a few of her children in a temporary shelter near the migrants’ camp in Nipomo, California, next to her broken-down car. The woman’s boyfriend, Jim, was away for several hours with the older two children to get the car’s radiator fixed.

While she waited, she was approached by an apparently friendly photographer named Dorothea Lange, who was touring the Central Valley at the request of the federal government to document the plight of migrant laborers.

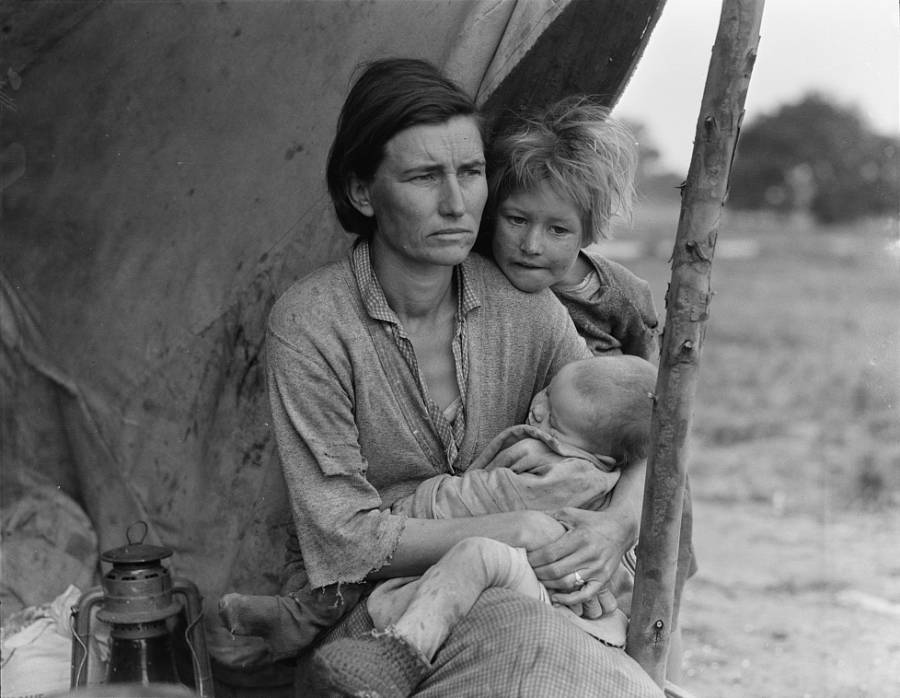

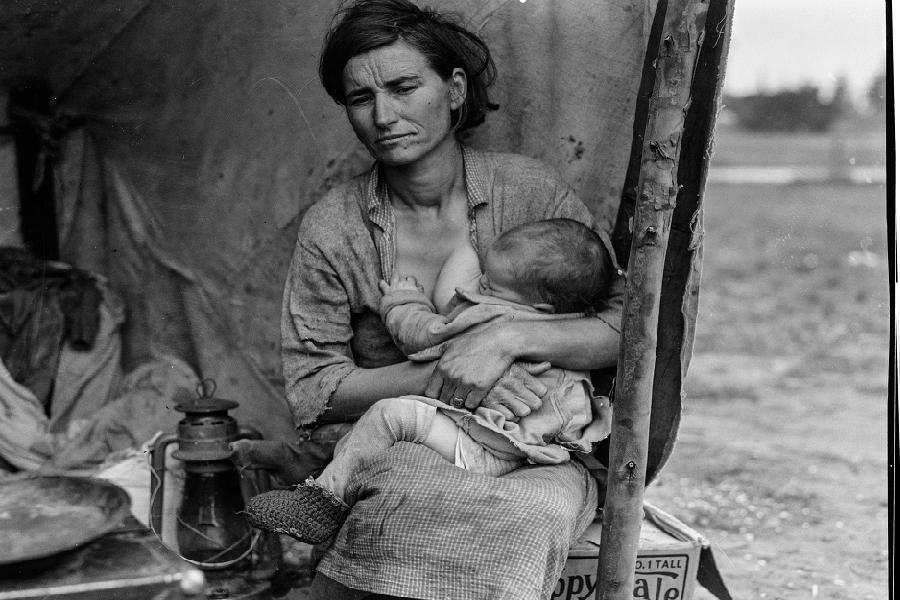

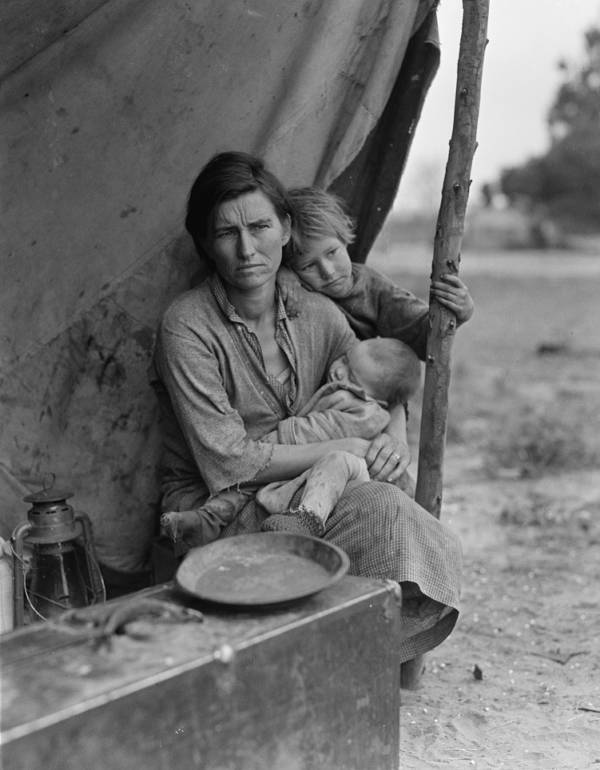

In ten minutes, Lange snapped six photos of Owens and her children. Together — with the photo above chief among them — these “Migrant Mother” photos became the definitive images of Depression-era poverty and despair.

The photos, which were commissioned by the government and thus in the public domain, quickly spread through multiple newspapers and magazines, but none of the readers at the time ever got the real story of the iconic “Migrant Mother” photos.

On The Way To California

Florence Christie was born in 1903 in what was then the Indian Territory and is now Oklahoma. She never knew her father; he had abandoned Christie’s mother during her pregnancy and never came back.

Indian Territory in 1903 wasn’t the place for a single mother with a newborn, and Christie’s mother quickly married a Choctaw man named Charles Akman. They seem to have lived a happy life together until 1921, when the 17-year-old Christie left home to marry her first husband, Cleo Owens.

Ten years and six children later, after the family had moved to California to find work in the mills, he died of tuberculosis. Florence Owens was now the widowed mother of six children in the Great Depression.

To make ends meet, Owens worked at whatever jobs shoe could find, from waitress to field hand. During this time, she had another child by a male friend. According to one of her daughters, interviewed many years later:

We never had a lot, but she always made sure we had something. She didn’t eat sometimes, but she made sure us children ate.

After bouncing around for a while, Owens met Jim Hill, who would father three more of her children. To support their family, Owens and Hill moved from one agricultural job to the next, sometimes in California, sometimes in Arizona, moving with the harvest to maintain steady work.

It was while they were driving through southern California to pick peas that the car broke down, which was just as well, since an early frost had killed the crop and something like 3,000 other workers who had come out now had nothing to do.

The Day Of The Photos

On the day of the photos, Dorothea Lange was visiting the Nipomo migrants’ camp to document the workers’ lives when she just happened to notice Owens setting up her shelter by the road.

Hill and the two older boys had a long walk to make into town, and they weren’t expected back before dark, so Owens had started supper. Lange introduced herself, the two women chatted for a while, and Lange took the photos.

According to Owens, Lange promised not to distribute the photos and never asked about her past. Lange’s notes from the meeting read:

Seven hungry children. Father is native Californian. Destitute in pea pickers’ camp. . . because of failure of the early pea crop. These people had just sold their tires to buy food.

Lange got several details wrong, and in later years Owens speculated that the photographer might have confused her with another woman.

For example, the family had not sold their tires; the car would need them when Hill got back with the radiator. The children may or may not have been hungry; Owens claimed that they had been boiling frozen peas and eating birds that the boys caught in the fields. They weren’t even properly in the pea pickers’ camp; their plan had been to swing past and keep moving toward Watsonville.

The Photos Go Viral

Despite Lange’s promise not to publish the photos, she filed them with the Federal Resettlement Administration and mailed a copy to the San Francisco News almost as soon as she got the chance.

The News ran the now iconic photo (that last of the six that Lange took) with Lange’s inaccurate details and reported that thousands of migrant farm laborers were starving in the San Joaquin Valley. Almost at once, readers of the paper began sending in donations so that poor could buy food. The government swung into action right away as well. Something like 20,000 pounds of food were immediately shipped to Nipomo to relieve what looked in the papers like a developing famine.

Owens and her family weren’t there to eat it. By the time the first parcel arrived, the family had moved on. Before long, the photo ran in national dailies and in magazines across the country. Everybody was looking at Owens’ worried expression and seeing the whole economic mess of the decade summed up in the lines of her face.

Everybody except for Owens, that is. In fact, she later claimed never to have seen the photos, though Lange had promised to send her copies, and nobody had ever recognized her from what was arguably the decade’s signature photograph.

Life For Florence Owens Thompson After The “Migrant Mother” Photos

Owens’ life stabilized in middle age. After World War II, she married a hospital administrator in Modesto, California named George Thompson. He made enough money to support his wife, now known as Florence Owens Thompson, at a reasonable level, and in later years her now-grown children pooled their money and bought her a house in Modesto.

Oddly, Owens Thompson later sold the house, explaining that she preferred living in a trailer. It was in that trailer in 1978 that a reporter for the Modesto Bee caught up with her and showed her the photo that had made her unwittingly famous.

The feature ran in the Bee and on the AP under the title: “Woman Fighting Mad Over Famous Depression Photo.” She really wasn’t, but “Mother Slightly Miffed She’s Been the Face of Poverty For Decades Without Knowing It” probably didn’t fit.

The “Migrant Mother” photo never made any money for Dorothea Lange. Per her contract with the government, the photos she took became the property of the government, and she wasn’t entitled to sell any of them. The photographs were good for her reputation, however, and she went on to a reasonably successful career later on.

The original negatives were nearly destroyed when somebody at the San Jose Chamber of Commerce threw them out. After being fished out of the dumpster behind the Chamber’s building, and sitting in an attic for 30 years, the negatives sold at auction for $296,000. In 1998, “Migrant Mother” was chosen for a stamp to commemorate the 1930s.

Florence Owens Thompson didn’t live to see any of this. In the early 1980s, her daughters announced that their mother was sick with cancer and a non-specific heart condition.

She died in her trailer in 1983, age 79, and was quietly buried in Modesto. Her headstone reads:

FLORENCE LEONA THOMPSON Migrant Mother – A Legend of the Strength of American Motherhood.

No comments: