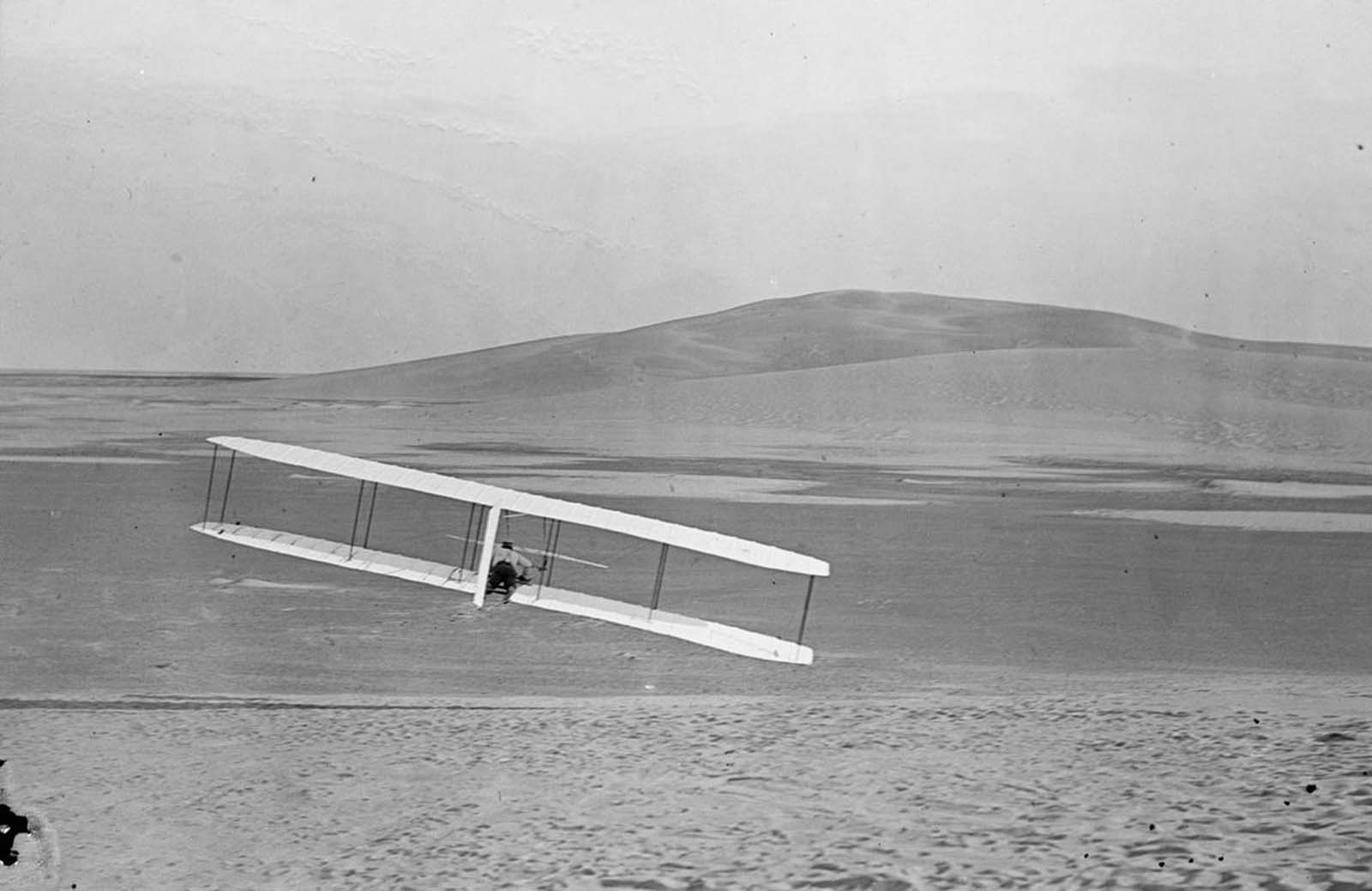

First flight with the Wright Brothers, 1902-1909

Wilbur Wright pilots a full-size glider down the steep slope of Big Kill Devil Hill in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on October 10, 1902. This model was the third iteration of the Wright brothers’ early gliders, equipped with wings that would warp to steer, a rear vertical rudder, and a forward elevator.

On December 17, 1903, Orville Wright piloted the first powered airplane 20 feet above a wind-swept beach in North Carolina. The flight lasted 12 seconds and covered 120 feet. Three more flights were made that day with Orville’s brother Wilbur piloting the record flight lasting 59 seconds over a distance of 852 feet. The Wright brothers documented much of their early progress in photographs made on glass negatives. The Library of Congress holds many of these historic images, some of which are presented below.

Since 1899, Wilbur and Orville Wright had been scientifically experimenting with the concepts of flight. They labored in relative obscurity, while the experiments of Samuel Langley of the Smithsonian were followed in the press and underwritten by the War Department. Yet Langley, as others before him, had failed to achieve powered flight. They relied on brute power to keep their theoretically stable machines aloft, sending along a hapless passenger and hoping for the best.

From left, Orville and Wilbur Wright, in portraits taken in 1905, when they were 34 and 38 years

old.

It was the Wrights’ genius and vision to see that humans would have to fly their machines, that the problems of flight could not be solved from the ground. In Wilbur’s words, “It is possible to fly without motors, but not without knowledge and skill.” With over a thousand glides from atop Big Kill Devil Hill, the Wrights made themselves the first true pilots. These flying skills were a crucial component of their invention. Before they ever attempted powered flight, the Wright brothers were masters of the air.

Their glider experiments on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, though frustrating at times, had led them down the path of discovery. Through those experiments, they had solved the problem of sustained lift and more importantly they could now control an aircraft while in flight. The brothers felt they were now ready to truly fly. But first, the Wrights had to power their aircraft.

Side view of Dan Tate, left, and Wilbur Wright, right, flying the 1902 glider as a kite, on September 19, 1902.

Gasoline engine technology had recently advanced to where its use in airplanes was feasible. Unable to find a suitable lightweight commercial engine, the brothers designed their own. It was cruder and less powerful than Samuel Langley’s, but the Wrights understood that relatively little power was needed with efficient lifting surfaces and propellers.

Such propellers were not available, however. Scant relevant data could be derived from marine propeller theory. Using their air tunnel data, they designed the first efficient airplane propeller, one of their most original and purely scientific achievements.

Crumpled glider, wrecked by the wind, on Hill of the Wreck, on October 10, 1900.

Returning to their camp at the Kill Devil Hills, they mounted the engine on the new 40-foot, 605-pound Flyer with double tails and elevators. The engine drove two pusher propellers with chains, one crossed to make the props rotate in opposite directions to counteract a twisting tendency in flight. A balky engine and broken propeller shaft slowed them, until they were finally ready on December 14th.

In order to decide who would fly first, the brother tossed a coin. Wilbur won the coin toss, but lost his chance to be the first to fly when he oversteered with the elevator after leaving the launching rail. The flyer, climbed too steeply, stalled, and dove into the sand. The first flight would have to wait on repairs.

Orville Wright and Edwin H. Sines, neighbor and boyhood friend, filing frames in the back of the Wright bicycle shop in 1897.

Three days later, they were ready for the second attempt. The 27-mph wind was harder than they would have liked, since their predicted cruising speed was only 30-35 mph. The headwind would slow their groundspeed to a crawl, but they proceeded anyway. With a sheet, they signaled the volunteers from the nearby lifesaving station that they were about to try again. Now it was Orville’s turn.

Remembering Wilbur’s experience, he positioned himself and tested the controls. The stick that moved the horizontal elevator controlled climb and descent. The cradle that he swung with his hips warped the wings and swung the vertical tails, which in combination turned the machine. A lever controlled the gas flow and airspeed recorder. The controls were simple and few, but Orville knew it would take all his finesse to handle the new and heavier aircraft.

Start of a glide; Wilbur in motion at left holding one end of glider (rebuilt with single vertical rudder), Orville lying prone in machine, and Dan Tate at right, in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on October 10, 1902.

At 10:35, he released the restraining wire. The flyer moved down the rail as Wilbur steadied the wings. Just as Orville left the ground, John Daniels from the lifesaving station snapped the shutter on a preset camera, capturing the historic image of the airborne aircraft with Wilbur running alongside. Again, the flyer was unruly, pitching up and down as Orville overcompensated with the controls. But he kept it aloft until it hit the sand about 120 feet from the rail. Into the 27-mph wind, the groundspeed had been 6.8 mph, for a total airspeed of 34 mph. The brothers took turns flying three more times that day, getting a feel for the controls and increasing their distance with each flight. Wilbur’s second flight – the fourth and last of the day – was an impressive 852 feet in 59 seconds.

This was the real thing, transcending the powered hops and glides others had achieved. The Wright machine had flown. But it would not fly again; after the last flight it was caught by a gust of wind, rolled over, and damaged beyond easy repair. With their flying season over, the Wrights sent their father a matter-of-fact telegram reporting the modest numbers behind their epochal achievement.

Rear view of Wilbur making a right turn in glide from No. 2 Hill, right wing tipped close to the ground, October 24, 1902.

The Wright Flyer I, built in 1903, front view. This machine was the Wright brothers’ first powered aircraft. The airplane sported two 8 foot wooden propellers driven by a purpose-built 12 horsepower engine.

Wilbur Wright at the controls of the damaged Wright Flyer, on the ground after an unsuccessful trial on December 14, 1903, in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

First flight: 120 feet in 12 seconds, on December 17, 1903. This photograph shows man’s first powered, controlled, sustained flight. Orville Wright at the controls of the machine, lying prone on the lower wing with hips in the cradle which operated the wing-warping mechanism. Wilbur Wright running alongside to balance the machine, has just released his hold on the forward upright of the right wing. The starting rail, the wing-rest, a coil box, and other items needed for flight preparation are visible behind the machine. Orville Wright preset the camera and had John T. Daniels squeeze the rubber bulb, tripping the shutter.

Wilbur and Orville Wright with their second powered machine on Huffman Prairie, near Dayton, Ohio, in May of 1904.

Front view of flight 41, Orville flying to the left at a height of about 60 feet; Huffman Prairie, Dayton, Ohio, September 29, 1905.

The remodeled 1905 Wright machine, altered to allow the operator to assume a sitting position and to provide a seat for a passenger, on the launching track at Kill Devil Hills in 1908.

Troops of the U.S. Army Signal Corps rush to the site of a crashed plane to recover the pilot Orville Wright and his passenger, army observer Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge, from the wreckage on September 17, 1908, in Fort Myer, Virginia. The plane crashed during a demonstration flight at a military installation, making Lt. Selfridge, who died from his injuries, the first fatality of a military airplane crash. Orville suffered a broken left leg and four broken ribs.

Close-up view of a Wright airplane, including the pilot and passenger seats, 1911.

Wilbur Wright makes a 33-minute-long flight during the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York in 1909. Wright started from Governors Island to fly up the Hudson River to Grant’s Tomb and back, a feat witnessed by hundreds of thousands of New York residents.

Siblings Orville Wright, Katharine Wright, and Wilbur Wright at Pau, France. Miss Wright about to be taken for her first ride in an airplane. February 15, 1909.

Orville Wright during proving flights for the U.S. Army at Fort Myer, Virginia, in July of 1909. The Wright brothers were able to sell their airplane to the Army’s Aeronautical Division, U.S. Signal Corps

No comments: